"Trope" is one of those words used in the book (or academic) community, but not much anywhere else. One definition of a trope is a common or overused theme or device, a cliche. The most commonly criticized trope in book world is the love triangle: thank you Twilight. And Hunger Games. And ... well, you can probably name a few of your own. Of course, it was never really a triangle; wasn't it really a love "V" since almost never was there a third side to the triangle? For a triangle, Alyn has to love Bryn who loves Crys who loves Alyn. Now you have a love triangle! Write that (which is basically the plot of the movie Carrington with Emma Thompson). And isn't a love triangle actually either two people you're interested in, or you're cheating on someone?

But love triangles aren't what I'm here to talk about today. My most hated book trope is ... dreams. No, not your hopes and aspirations, that dream you have to lose 15 pounds. No, I'm talking about those odd pictures in your head while you're sleeping. Because authors use dreams in book after book after book. It's getting old. One of my issues is that half the time I don't get why the author put the dream into the story. What does it mean? Of course ever since Freud folks have been coming up with ideas, but if there's going to be a paragraph's worth of dreams in the book (or two or three pages!), then it should be significant to the plot. My other problem with writing a dream into the story is that it seems a cheap and easy plot device. A way to get weird, to put in some psychedelia, some wild writing. Or a way to sneak in some plot points without having to work them logically into the story.

So here's my challenge. In your reading, see how many books include a character dreaming about something. Then ask yourself: why is that dream in there? What's the author trying to do with that dream? And see if the author made as good use of the space devoted to that dream, as Van Gogh did.

Wednesday, August 31, 2016

Monday, August 29, 2016

Scream: A Memoir of Glamour and Dysfunction by Tama Janowitz (2016)

A memoir by the "Brat Pack" author of Slaves of New York.

Book Review: When I saw Scream: A Memoir of Glamour and Dysfunction, I'd been thinking of reading the '80s "Brat Pack" writers, Jay McInerny (Bright Lights, Big City), Bret Easton Ellis (Less Than Zero, American Psycho), and Tama Janowitz, so this new release seemed the perfect way to jump into that project. It wasn't. Scream is a good title for this memoir, as in those horror movies with the audience yelling "Don't go into the basement!" But of course our intrepid heroine traipses merrily down the stairs. In this memoir, Janowitz comes off as someone who makes emotional decisions, does what she wants, makes bad choices, and then is angry at the rest of the world when life doesn't go well. Maybe that's the life of an artist, but everyone else in Scream is evil, stupid, dangerous, or a burden (she's reported to Adult Protective Services for her treatment of her very supportive mother, who was a well-respected poet). She notes, "for me, other human beings are a blend of pit vipers, chimpanzees, and ants, a virtually indistinguishable mass of killer shit-kickers, sniffing their fingers and raping." Janowitz even attacks the innocent: in "Ithaca there are vegetarian academics who teach morons at the prestigious university" (where her mother taught for 30 years), and even people she doesn't know (such as friends and family members of acquaintances). No mercy: "When you hear someone talking about someone else who does the same thing you do but is more successful at it than you are, you want to squelch that other person." She acknowledges that she's one of the people "on this planet who irritate others," but doesn't change her behavior -- she's "used to people's anger." It's strange that she hates Catcher in the Rye, since she and Holden Caulfield seem to have a lot in common.

There's also an unpleasant settling of old scores: Janowitz "can't stand" her husband, so she cheats on him; her brother and sister-in-law, she gets them too; her boyfriend's girlfriend, bashes her; her teenage daughter smokes pot and doesn't want to travel to Jordan for a summer program, but Janowitz (now stuck with her daughter for the summer) just needs to "kick [her] behind and talk some sense into her" and so takes her to a psychiatrist -- poor kid. The score-settling extends from her boss at Mademoiselle ("I do not know how stupid she was") to Andy Warhol who didn't buy her gifts at flea markets (but bought her dinner), down to saying nasty things about the daughter of her building's doorman, neighbors, service workers, and flunkies. When she tries to iron but destroys a model's expensive blouse during a photo shoot, she writes a childish and nasty letter blaming everyone else. She has her mother call editors to get her stories published. When her first book fails it's the reviewer's fault, not the writer's (no subsequent books succeeded -- her second book Slaves of New York from '86 is the only one cited on the cover of Scream). Her mother's former colleagues at the university (y'know, the ones teaching the morons?) never invited her to teach there. There's a lot of how life was so much harder back in the day. Despite the subtitle, "A Memoir of Glamour and Dysfunction," the book focuses mostly on the dysfunction, and the glamour mostly seems seedy (19-year old Tama visiting and then sleeping with 63-year old Lawrence Durrell; yes she bashes him for it) or disappointing. I was hoping to get some insights into the writing, how that '80s style was created, but Janowitz doesn't like writing: "Writing, to me, was a living death," because "nothing is happening." She asks, "is that really a fun way to spend your life ... ?" No insights.

In fairness, some of the time Janowitz may have been trying to be funny, but beyond a few chuckles it wasn't that comedic. So much to say, but this book seems like it was rushed out to make a quick buck. While reading I couldn't help comparing Scream to Patti Smith's two excellent memoirs. Although Janowitz doesn't mention her Brooklyn (Park Slope) penthouse, she does briefly acknowledge the hardships of working class and older people, which I appreciated. Mostly this was just bitter, sad, and disappointing. But I'll still read Slaves of New York. [2 Stars]

Book Review: When I saw Scream: A Memoir of Glamour and Dysfunction, I'd been thinking of reading the '80s "Brat Pack" writers, Jay McInerny (Bright Lights, Big City), Bret Easton Ellis (Less Than Zero, American Psycho), and Tama Janowitz, so this new release seemed the perfect way to jump into that project. It wasn't. Scream is a good title for this memoir, as in those horror movies with the audience yelling "Don't go into the basement!" But of course our intrepid heroine traipses merrily down the stairs. In this memoir, Janowitz comes off as someone who makes emotional decisions, does what she wants, makes bad choices, and then is angry at the rest of the world when life doesn't go well. Maybe that's the life of an artist, but everyone else in Scream is evil, stupid, dangerous, or a burden (she's reported to Adult Protective Services for her treatment of her very supportive mother, who was a well-respected poet). She notes, "for me, other human beings are a blend of pit vipers, chimpanzees, and ants, a virtually indistinguishable mass of killer shit-kickers, sniffing their fingers and raping." Janowitz even attacks the innocent: in "Ithaca there are vegetarian academics who teach morons at the prestigious university" (where her mother taught for 30 years), and even people she doesn't know (such as friends and family members of acquaintances). No mercy: "When you hear someone talking about someone else who does the same thing you do but is more successful at it than you are, you want to squelch that other person." She acknowledges that she's one of the people "on this planet who irritate others," but doesn't change her behavior -- she's "used to people's anger." It's strange that she hates Catcher in the Rye, since she and Holden Caulfield seem to have a lot in common.

There's also an unpleasant settling of old scores: Janowitz "can't stand" her husband, so she cheats on him; her brother and sister-in-law, she gets them too; her boyfriend's girlfriend, bashes her; her teenage daughter smokes pot and doesn't want to travel to Jordan for a summer program, but Janowitz (now stuck with her daughter for the summer) just needs to "kick [her] behind and talk some sense into her" and so takes her to a psychiatrist -- poor kid. The score-settling extends from her boss at Mademoiselle ("I do not know how stupid she was") to Andy Warhol who didn't buy her gifts at flea markets (but bought her dinner), down to saying nasty things about the daughter of her building's doorman, neighbors, service workers, and flunkies. When she tries to iron but destroys a model's expensive blouse during a photo shoot, she writes a childish and nasty letter blaming everyone else. She has her mother call editors to get her stories published. When her first book fails it's the reviewer's fault, not the writer's (no subsequent books succeeded -- her second book Slaves of New York from '86 is the only one cited on the cover of Scream). Her mother's former colleagues at the university (y'know, the ones teaching the morons?) never invited her to teach there. There's a lot of how life was so much harder back in the day. Despite the subtitle, "A Memoir of Glamour and Dysfunction," the book focuses mostly on the dysfunction, and the glamour mostly seems seedy (19-year old Tama visiting and then sleeping with 63-year old Lawrence Durrell; yes she bashes him for it) or disappointing. I was hoping to get some insights into the writing, how that '80s style was created, but Janowitz doesn't like writing: "Writing, to me, was a living death," because "nothing is happening." She asks, "is that really a fun way to spend your life ... ?" No insights.

In fairness, some of the time Janowitz may have been trying to be funny, but beyond a few chuckles it wasn't that comedic. So much to say, but this book seems like it was rushed out to make a quick buck. While reading I couldn't help comparing Scream to Patti Smith's two excellent memoirs. Although Janowitz doesn't mention her Brooklyn (Park Slope) penthouse, she does briefly acknowledge the hardships of working class and older people, which I appreciated. Mostly this was just bitter, sad, and disappointing. But I'll still read Slaves of New York. [2 Stars]

Saturday, August 27, 2016

Changeless by Gail Carriger (2010)

The second book in Gail Carriger's Parasol Protectorate series with Alexia Tarabotti.

Book Review: If you enjoyed Soulless, there's no reason why you wouldn't enjoy this one, and I'm not even sure why you'd be reading Changeless if you hadn't read the first book. This is more of the same: a humorous take on werewolves, vampires, bustles, and ladies' hats in 1870s Victorian England. This time Alexia, Ivy, and Felicity take a trip to Scotland on a dirigible. For Changeless Gail Carriger has added more werewolves than vampires, much more steampunk than the first (and some James Bondian toys are added -- guess where), a little less romance (much less of the steamy variety -- ah, marriage). And it's very English: "'But why Scotland. I should hate to have to go to Scotland. It is such a barbaric place. It is practically Ireland!'" There's a bit of mystery and thriller involved as usual with Carriger, with much tea drinking, and although the pace is sedate as befits Victorian England, the story and humor keep the reader reading. This is light, fun entertainment, as long as you don't expect too much literary excellence mixed in with the enjoyment; Changeless somehow simultaneously combines inconsistent and (mostly) flat characters, but it's not a serious distraction as long as you're willing to roll with it. And the fun is good fun -- off to find volume three today! [3 Stars]

Book Review: If you enjoyed Soulless, there's no reason why you wouldn't enjoy this one, and I'm not even sure why you'd be reading Changeless if you hadn't read the first book. This is more of the same: a humorous take on werewolves, vampires, bustles, and ladies' hats in 1870s Victorian England. This time Alexia, Ivy, and Felicity take a trip to Scotland on a dirigible. For Changeless Gail Carriger has added more werewolves than vampires, much more steampunk than the first (and some James Bondian toys are added -- guess where), a little less romance (much less of the steamy variety -- ah, marriage). And it's very English: "'But why Scotland. I should hate to have to go to Scotland. It is such a barbaric place. It is practically Ireland!'" There's a bit of mystery and thriller involved as usual with Carriger, with much tea drinking, and although the pace is sedate as befits Victorian England, the story and humor keep the reader reading. This is light, fun entertainment, as long as you don't expect too much literary excellence mixed in with the enjoyment; Changeless somehow simultaneously combines inconsistent and (mostly) flat characters, but it's not a serious distraction as long as you're willing to roll with it. And the fun is good fun -- off to find volume three today! [3 Stars]

Thursday, August 25, 2016

Soulless by Gail Carriger (2009)

The first in the charming and entertaining Parasol Protectorate series.

Book Review: Soulless is a comedic, Victorian, paranormal, romance leavened with a bit of steampunk. The pseudonymous Gail Carriger seems to have checked a few of the required boxes. The spinsterish (all of 26!) Alexia Tarabotti has a certain condition (hence the title!) that helps in dealing with the vampires and werewolves that have integrated into British society (they're still outcasts in the colonies). But now some of the supernatural creatures seem to be disappearing and others are acting most inappropriately. Miss Tarabotti is caught up in the midst of a London replete with hunky werewolves, gay vampires, and Victorian mores (the Queen even makes a cameo!). Soulless is all good fun, charming entertainment, deliberately paced but a quick read, with plenty of chuckles to be found, and Austenish touches to boot -- Gail Carriger does it all. Not a lot happens, but all of it is enjoyable. Alexia is charming, romantic, heroic -- a character for our times, or those times, or any times. At times Carriger has problems with maintaining tone (Alexia breaks character occasionally) and balancing the Victorian with the paranormal, but all in all this was a fun read and refreshingly entertaining. And certainly different for me. If curious if this is for you, read the first couple of pages of Soulless and you'll know. A good summer-read, beach-read kind of thing; I'm reading the second one (Changeless) now. [3.5 Stars]

Book Review: Soulless is a comedic, Victorian, paranormal, romance leavened with a bit of steampunk. The pseudonymous Gail Carriger seems to have checked a few of the required boxes. The spinsterish (all of 26!) Alexia Tarabotti has a certain condition (hence the title!) that helps in dealing with the vampires and werewolves that have integrated into British society (they're still outcasts in the colonies). But now some of the supernatural creatures seem to be disappearing and others are acting most inappropriately. Miss Tarabotti is caught up in the midst of a London replete with hunky werewolves, gay vampires, and Victorian mores (the Queen even makes a cameo!). Soulless is all good fun, charming entertainment, deliberately paced but a quick read, with plenty of chuckles to be found, and Austenish touches to boot -- Gail Carriger does it all. Not a lot happens, but all of it is enjoyable. Alexia is charming, romantic, heroic -- a character for our times, or those times, or any times. At times Carriger has problems with maintaining tone (Alexia breaks character occasionally) and balancing the Victorian with the paranormal, but all in all this was a fun read and refreshingly entertaining. And certainly different for me. If curious if this is for you, read the first couple of pages of Soulless and you'll know. A good summer-read, beach-read kind of thing; I'm reading the second one (Changeless) now. [3.5 Stars]

Monday, August 22, 2016

Lady Susan, The Watsons, Sanditon by Jane Austen (1871)

A novella and two fragments written by Jane Austen (1775-1817) at three different points in her writing life.

Book Review: Yes, because of the recent film Love and Friendship, I resolved to read Lady Susan (the source for the film, not Austen's story "Love and Friendship," as might be expected). This precocious novella, consisting only of letters written among the characters, was drafted early in Austen's career, perhaps around 1793-4, with a "final" draft copied out around 1805, although it wasn't published in Austen's lifetime. What first becomes clear after reading, is how much and how well director and "co-writer" Whit Stillman added to the story.

What is also striking is what a unique character Lady Susan is for Austen, and wonderfully so. This quickly became a favorite. Margaret Drabble refers to Lady Susan's "excessive wickedness," which seems a bit much. She's also called "ruthless" and "unscrupulous," when in fact she is simply doing what she needs to do, given the tools available to her, to control her life and live as she chooses, as others were free to do at the time. She may be fierce and savage, but in a good cause. Lady Susan writes: "I am tired of submitting my will to the caprices of others -- of resigning my own judgement in deference to those, to whom I owe no duty, and for whom I feel no respect. I have given up too much." Do we hear Jane Austen? Some say she is cruel to her daughter, but only because the foolish and penniless girl wants to marry for love when she can become rich by marrying the suitor her mother found for her. I found the character of Lady Susan, who I think is Jane Austen unbound, even more interesting than the eponymous novella. It's intriguing to speculate what Austen (who may have written it at 18) might have done with this irresistible character when her writing skills were more developed, if she had felt more free to release an uninhibited Lady Susan on the world, and if unconstrained by the limits of the already outdated epistolary style. For the style hindered the story; I wished for more and different correspondents to broaden and spice the story. And without being straitjacketed by the postal system, the ending could have been less forced and hasty. Stillman's film gives some idea of where Austen might have gone with the characters.

The other two fragments contained in the book are mostly a tease, and neither was completed or published in her lifetime. The Watsons, written after the first drafts of Austen's early novels but prior to their publication, seems much like a traditional Austen, a disappointed heiress, the necessity of a good match, the affectations of the stylish. Although written with wit and humor, it leaves the reader wondering what may have come next, and is only for Austen completists who feel that any bit of Jane is worth seeking out. Sanditon, however, the last of Austen's writing, written shortly before her death, is something new for Austen and may have pointed to a more contemporary outlook, considering both the focus on "speculation" in a seaside town, and that one of the characters is "half mulatto," which took me aback when I read it. Is this our Jane? What Austen might have done with this should lead to lively conversation. I enjoyed all three stories, but enjoyed all three more for what might've been, than what is fully upon the page. [3.5 Stars]

Book Review: Yes, because of the recent film Love and Friendship, I resolved to read Lady Susan (the source for the film, not Austen's story "Love and Friendship," as might be expected). This precocious novella, consisting only of letters written among the characters, was drafted early in Austen's career, perhaps around 1793-4, with a "final" draft copied out around 1805, although it wasn't published in Austen's lifetime. What first becomes clear after reading, is how much and how well director and "co-writer" Whit Stillman added to the story.

What is also striking is what a unique character Lady Susan is for Austen, and wonderfully so. This quickly became a favorite. Margaret Drabble refers to Lady Susan's "excessive wickedness," which seems a bit much. She's also called "ruthless" and "unscrupulous," when in fact she is simply doing what she needs to do, given the tools available to her, to control her life and live as she chooses, as others were free to do at the time. She may be fierce and savage, but in a good cause. Lady Susan writes: "I am tired of submitting my will to the caprices of others -- of resigning my own judgement in deference to those, to whom I owe no duty, and for whom I feel no respect. I have given up too much." Do we hear Jane Austen? Some say she is cruel to her daughter, but only because the foolish and penniless girl wants to marry for love when she can become rich by marrying the suitor her mother found for her. I found the character of Lady Susan, who I think is Jane Austen unbound, even more interesting than the eponymous novella. It's intriguing to speculate what Austen (who may have written it at 18) might have done with this irresistible character when her writing skills were more developed, if she had felt more free to release an uninhibited Lady Susan on the world, and if unconstrained by the limits of the already outdated epistolary style. For the style hindered the story; I wished for more and different correspondents to broaden and spice the story. And without being straitjacketed by the postal system, the ending could have been less forced and hasty. Stillman's film gives some idea of where Austen might have gone with the characters.

The other two fragments contained in the book are mostly a tease, and neither was completed or published in her lifetime. The Watsons, written after the first drafts of Austen's early novels but prior to their publication, seems much like a traditional Austen, a disappointed heiress, the necessity of a good match, the affectations of the stylish. Although written with wit and humor, it leaves the reader wondering what may have come next, and is only for Austen completists who feel that any bit of Jane is worth seeking out. Sanditon, however, the last of Austen's writing, written shortly before her death, is something new for Austen and may have pointed to a more contemporary outlook, considering both the focus on "speculation" in a seaside town, and that one of the characters is "half mulatto," which took me aback when I read it. Is this our Jane? What Austen might have done with this should lead to lively conversation. I enjoyed all three stories, but enjoyed all three more for what might've been, than what is fully upon the page. [3.5 Stars]

Friday, August 19, 2016

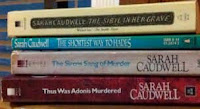

Sarah Caudwell: Four Best Mysteries

My favorite mystery writer is not Arthur Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie, or Raymond Chandler. It's the precious and inimitable Sarah Caudwell.

Sarah Caudwell was the pseudonym of Sarah Cockburn (1939-2000), born in England of Scottish descent, who studied law at Oxford, was a member of the Chancery Bar, and practiced as a barrister in Lincoln's Inn (writer Alexander Cockburn was her half-brother). As Caudwell she wrote four charming novels published from 1981 to 2000, all dryly humorous cozy mysteries, very legal, very arch, and very English, involving four members of the Bar and their good friend, amateur detective and noted Scholar, Oxford law professor Hilary Tamar. The four novels are Thus was Adonis Murdered (1981), The Shortest Way to Hades (1984), The Sirens Sang of Murder (1989), and The Sibyl in Her Grave (2000). Although far from necessary, I'd suggest reading them in chronological order. In any event, read them.

An essential part of the books are the four personable members of the Bar, plus one, who compose the detective team. There's the curvy and amorous Julia Larwood, always a mess but determinedly sweet, clumsy, and well-intentioned. Selena Jardine, professional, beautiful, endlessly capable, and always protective of dear Julia. There's the callow, oblivious, but sturdy Michael Cantrip, and his good friend Desmond Ragwort, he of the perfect profile, always properly decorous and upright. And of course the noted Scholar, the indeterminate Professor Hilary Tamar.

Throughout the four books, Caudwell never identified Professor Tamar by gender, female or male, gay or straight. It's a mystery. For readers who don't pick up on this, it's always entertaining to see which gender they assign the good Professor. In her last book, The Sibyl in Her Grave, Caudwell has a little fun with this added mystery, as Professor Tamar says:

Readers may well wonder which of these precious volumes is the best and I don't have an answer for you. You'll probably say that I'm failing in my duty as a reviewer, and I don't like to think of you being so judgmental -- you used to be such nice readers. Truth is, I really think of them all as a unified piece, as having a single personality, four chapters of one book. The first, Thus was Adonis Murdered, certainly won me over, so that might be my favorite, tho it has Caudwell's most rarefied language. The last, The Sibyl in Her Grave, has the most convoluted mystery, but has an air of being not quite finished. So maybe it's The Shortest Way to Hades? Who knows? They're all good.

Despite my love for these books, I fear they will be lost to time. Agatha Christie wrote so many noted books that her work will live forever, but Caudwell wrote only four novels, which may be easily forgotten. In the best of all possible worlds, some far-sighted publisher would reissue these books, perhaps all four in a single volume, or two volumes of two books each, or a box set, with a laudatory introduction by some noted mystery writer of today. With a little promotion and some judicious word of mouth, this would be great addition to the canon of worthy mystery novels.

Search thrift stores, charity shops, used-book stores. Check your library. Go on-line. Find these books. You can thank me later. You're welcome.

Sarah Caudwell was the pseudonym of Sarah Cockburn (1939-2000), born in England of Scottish descent, who studied law at Oxford, was a member of the Chancery Bar, and practiced as a barrister in Lincoln's Inn (writer Alexander Cockburn was her half-brother). As Caudwell she wrote four charming novels published from 1981 to 2000, all dryly humorous cozy mysteries, very legal, very arch, and very English, involving four members of the Bar and their good friend, amateur detective and noted Scholar, Oxford law professor Hilary Tamar. The four novels are Thus was Adonis Murdered (1981), The Shortest Way to Hades (1984), The Sirens Sang of Murder (1989), and The Sibyl in Her Grave (2000). Although far from necessary, I'd suggest reading them in chronological order. In any event, read them.

An essential part of the books are the four personable members of the Bar, plus one, who compose the detective team. There's the curvy and amorous Julia Larwood, always a mess but determinedly sweet, clumsy, and well-intentioned. Selena Jardine, professional, beautiful, endlessly capable, and always protective of dear Julia. There's the callow, oblivious, but sturdy Michael Cantrip, and his good friend Desmond Ragwort, he of the perfect profile, always properly decorous and upright. And of course the noted Scholar, the indeterminate Professor Hilary Tamar.

Throughout the four books, Caudwell never identified Professor Tamar by gender, female or male, gay or straight. It's a mystery. For readers who don't pick up on this, it's always entertaining to see which gender they assign the good Professor. In her last book, The Sibyl in Her Grave, Caudwell has a little fun with this added mystery, as Professor Tamar says:

"Some of my readers ... have been kind enough to say that they would like to know more about me -- what I look like, how I dress ... and other details of a personal and sometimes even intimate nature. I do not doubt, however, that these enquiries are made purely as a matter of courtesy. Maintaining, therefore, that modest reticence which I think becoming to the historian, I shall say no more of myself ... ."Caudwell's dry humor is the ornament that brightens the mysteries at the core of these novels. You can't have one without the other in these books, and both are perfectly wonderful. Her lines are so arch that the reader can zip right by, not noting the zinger just missed. Devour slowly for maximum flavor.

Readers may well wonder which of these precious volumes is the best and I don't have an answer for you. You'll probably say that I'm failing in my duty as a reviewer, and I don't like to think of you being so judgmental -- you used to be such nice readers. Truth is, I really think of them all as a unified piece, as having a single personality, four chapters of one book. The first, Thus was Adonis Murdered, certainly won me over, so that might be my favorite, tho it has Caudwell's most rarefied language. The last, The Sibyl in Her Grave, has the most convoluted mystery, but has an air of being not quite finished. So maybe it's The Shortest Way to Hades? Who knows? They're all good.

Despite my love for these books, I fear they will be lost to time. Agatha Christie wrote so many noted books that her work will live forever, but Caudwell wrote only four novels, which may be easily forgotten. In the best of all possible worlds, some far-sighted publisher would reissue these books, perhaps all four in a single volume, or two volumes of two books each, or a box set, with a laudatory introduction by some noted mystery writer of today. With a little promotion and some judicious word of mouth, this would be great addition to the canon of worthy mystery novels.

Search thrift stores, charity shops, used-book stores. Check your library. Go on-line. Find these books. You can thank me later. You're welcome.

Wednesday, August 17, 2016

The Sybil in Her Grave by Sarah Caudwell (2000)

The tax collector is knocking loudly at her door, has Julia's beloved Aunt Reg benefited from insider trading? Only noted Scholar Hilary Tamar can save the day!

Book Review: The fourth and, sadly, final book in Sarah Caudwell's archly humorous take on the cozy English mystery, The Sibyl in Her Grave, ranks right up there with the first three -- winners all. This one is a little easier to read, the language a bit simpler, and the story is more tortuous than ever. As usual, half the story is told in letters, as the usual crew of Julia, Selena, Cantrip, Ragwort, and the suitably vague Professor Tamar look into Aunt Regina's tax problems, only to find insider trading, poisonings, and hidden identities. Here we get to see a wee bit more than we have previously of the ineffably handsome and proper Desmond Ragwort. The Sybil in Her Grave has much wine drinking, fortune telling, endless refurbishing, and more than before, love, and of course those pesky inexplicable deaths. As Professor Tamar says, "few questions are impenetrable to the mind of the trained Scholar," and members of the Chancery Bar travel from London to Cannes to Oxford to a seemingly innocent village in West Sussex as the mystery takes twists and turns and the reader chases leads that dissolve before the eyes. The Sybil in Her Grave has so many strengths, the wonderfully entertaining characters from curvy and clumsy Julia to the callow Cantrip, the very Englishness of it, and the convoluted mystery itself. But for me the greatest joy lies in Sarah Caudwell's dry humor that slips by unseen unless paying sharp attention:

Book Review: The fourth and, sadly, final book in Sarah Caudwell's archly humorous take on the cozy English mystery, The Sibyl in Her Grave, ranks right up there with the first three -- winners all. This one is a little easier to read, the language a bit simpler, and the story is more tortuous than ever. As usual, half the story is told in letters, as the usual crew of Julia, Selena, Cantrip, Ragwort, and the suitably vague Professor Tamar look into Aunt Regina's tax problems, only to find insider trading, poisonings, and hidden identities. Here we get to see a wee bit more than we have previously of the ineffably handsome and proper Desmond Ragwort. The Sybil in Her Grave has much wine drinking, fortune telling, endless refurbishing, and more than before, love, and of course those pesky inexplicable deaths. As Professor Tamar says, "few questions are impenetrable to the mind of the trained Scholar," and members of the Chancery Bar travel from London to Cannes to Oxford to a seemingly innocent village in West Sussex as the mystery takes twists and turns and the reader chases leads that dissolve before the eyes. The Sybil in Her Grave has so many strengths, the wonderfully entertaining characters from curvy and clumsy Julia to the callow Cantrip, the very Englishness of it, and the convoluted mystery itself. But for me the greatest joy lies in Sarah Caudwell's dry humor that slips by unseen unless paying sharp attention:

"I was under the impression ... that the Church nowadays no longer believed in hell."or,

"We no longer believe in it as a geographical place, like Paris or Los Angeles. Not, of course, that one ever thought that it would be anything like Paris."

"Daphne and I are now bosom friends. That is to say, she seems to think we are; and I do not feel that I know her well enough to dispute it."The pages are littered with arch throw-away lines that tickle me endlessly. I did wonder about the provenance of this one, and whether Caudwell actually completed it. The first three books came out over an eight year period, but this one showed up about 11 years later, the year she died. I enjoyed The Sibyl in Her Grave as much as any of Sarah Caudwell's other three mysteries, which is to say, immensely -- right up my street! My only sorrow is that never again will I hear my beloved Professor Tamar say, "the insights of Scholarship are neither to be purchased by bribes not compelled by threats." [4 Stars]

Monday, August 15, 2016

Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World by Haruki Murakami (1985)

Two disrupted lives in two very different worlds in which fantasy and reality intersect, until the two worlds begin to connect.

Book Review: Haruki Murakami's Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World consists of two alternating stories: the first, with a naive human calculator, set in the seeming reality of Hard-Boiled Wonderland, which initially is much like our world but becomes seriously different sci-fi; and the second about an amnesiac newcomer to the fanciful End of the World, a land of unicorns and dreamreaders, but with moments of human familiarity. Despite the disparate landscapes, there are a number of similarities between the two worlds: both involve a librarian, music, a unicorn skull, shadows, and both raise as many questions as they answer. The first story, Hard-Boiled Wonderland, has elements in which Raymond Chandler meets Alice in a sci-fi mashup with hints of The Maltese Falcon. At times the story set at the End of the World reminded me of The Golden Compass, (Northern Lights in the UK), by Philip Pullman (which I loved), tho Murakami's book (his fourth novel) was published years earlier. I have no idea if Pullman read this, but the similarity of certain themes was intriguing, watching how two highly creative minds worked with such ideas. In the end, I enjoyed Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World more on an intellectual than an emotional level, more as a puzzle than a tale (the map of the End of the World resembles a brain). Two good stories (which the reader prefers is a Rorschach test) with interesting and complexly interrelated structures, but I wasn't personally drawn in the way I usually am with a Murakami novel. Perhaps there wasn't enough reality initially for me to identify with (I haven't read a lot of fantasy); Harry and Hermione seemed more real to me. Then again, the protagonist(s) aren't overly emotional either. I should also note that the ending isn't easy or simple, and may be another Rorschach moment. The translation, by Alfred Birnbaum, seemed to have more than the usual number of "right word?" moments, but wasn't problematic. Still an enjoyable read, and his fourth novel is a worthy part of the Murakami canon. And it contains a great simile: "asleep like a tuna." [4 Stars]

Book Review: Haruki Murakami's Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World consists of two alternating stories: the first, with a naive human calculator, set in the seeming reality of Hard-Boiled Wonderland, which initially is much like our world but becomes seriously different sci-fi; and the second about an amnesiac newcomer to the fanciful End of the World, a land of unicorns and dreamreaders, but with moments of human familiarity. Despite the disparate landscapes, there are a number of similarities between the two worlds: both involve a librarian, music, a unicorn skull, shadows, and both raise as many questions as they answer. The first story, Hard-Boiled Wonderland, has elements in which Raymond Chandler meets Alice in a sci-fi mashup with hints of The Maltese Falcon. At times the story set at the End of the World reminded me of The Golden Compass, (Northern Lights in the UK), by Philip Pullman (which I loved), tho Murakami's book (his fourth novel) was published years earlier. I have no idea if Pullman read this, but the similarity of certain themes was intriguing, watching how two highly creative minds worked with such ideas. In the end, I enjoyed Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World more on an intellectual than an emotional level, more as a puzzle than a tale (the map of the End of the World resembles a brain). Two good stories (which the reader prefers is a Rorschach test) with interesting and complexly interrelated structures, but I wasn't personally drawn in the way I usually am with a Murakami novel. Perhaps there wasn't enough reality initially for me to identify with (I haven't read a lot of fantasy); Harry and Hermione seemed more real to me. Then again, the protagonist(s) aren't overly emotional either. I should also note that the ending isn't easy or simple, and may be another Rorschach moment. The translation, by Alfred Birnbaum, seemed to have more than the usual number of "right word?" moments, but wasn't problematic. Still an enjoyable read, and his fourth novel is a worthy part of the Murakami canon. And it contains a great simile: "asleep like a tuna." [4 Stars]

Monday, August 8, 2016

Sweet Tooth by Ian McEwan (2012)

A recent university graduate is recruited by MI5 to contact a young writer, love and plot ensue.

Book Review: Sweet Tooth was my first book by Ian McEwan; I'm not sure we had the best introduction. The book was written well enough, tho some stretches took patience to keep reading. I felt there were parts where there wasn't a lot going on, but I was reading to see when something else interesting was going to come along, and it usually did. I've heard such good things about the author that I felt I had to keep reading. McEwan is a good writer and intelligent, but here he seemed too clever by half. There are tricks and cleverness in Sweet Tooth, but does that make a good book? Gillian Flynn made a book out of it, but I'm not sure if that's who McEwan is patterning himself after. In genre fiction, especially short fiction, the surprise ending seems to be accepted: the mystery novel where the murderer turns out to be the narrator, the sci-fi story where the wily enemy is AI created by a long vanished civilization. But more serious literature doesn't usually rely on such techniques. Maybe McEwan just wanted to write a spy novel beach read, I don't know. But I do know I want to read more by McEwan, Atonement and some of his early stories in particular, and maybe this just wasn't the right time for me to read Sweet Tooth. I may do a re-read, and I'll keep thinking about my opinion on surprise endings as a literary device (how is this a book meant to last? once knowing the surprise, why ever read it again?). I'm sure there's a place for such stories, just not sure where that place is. [3 Stars]

Book Review: Sweet Tooth was my first book by Ian McEwan; I'm not sure we had the best introduction. The book was written well enough, tho some stretches took patience to keep reading. I felt there were parts where there wasn't a lot going on, but I was reading to see when something else interesting was going to come along, and it usually did. I've heard such good things about the author that I felt I had to keep reading. McEwan is a good writer and intelligent, but here he seemed too clever by half. There are tricks and cleverness in Sweet Tooth, but does that make a good book? Gillian Flynn made a book out of it, but I'm not sure if that's who McEwan is patterning himself after. In genre fiction, especially short fiction, the surprise ending seems to be accepted: the mystery novel where the murderer turns out to be the narrator, the sci-fi story where the wily enemy is AI created by a long vanished civilization. But more serious literature doesn't usually rely on such techniques. Maybe McEwan just wanted to write a spy novel beach read, I don't know. But I do know I want to read more by McEwan, Atonement and some of his early stories in particular, and maybe this just wasn't the right time for me to read Sweet Tooth. I may do a re-read, and I'll keep thinking about my opinion on surprise endings as a literary device (how is this a book meant to last? once knowing the surprise, why ever read it again?). I'm sure there's a place for such stories, just not sure where that place is. [3 Stars]

Friday, August 5, 2016

Joe Gould's Secret by Joseph Mitchell (1996)

A compilation of two New Yorker Profiles written by legendary journalist Joseph Mitchell about Greenwich Village bohemian and eccentric, Joe Gould (1889-1957).

Book Review: Unfortunately, I read Jill Lepore's book Joe Gould's Teeth (2016) prior to reading Joe Gould's Secret by Joseph Mitchell. Actually, I read this because of Lepore's book, which was a response to Mitchell's articles. If you have the choice, read JG's Secret before reading JG's Teeth, and you'll have a better view of the whole picture here; in a better world, all three works would be reissued in a single volume. Joseph Mitchell wrote two New Yorker articles about Joe Gould. The first was "Professor Sea Gull," in 1942, which made Gould (at least locally) famous and enabled him to survive above a bare subsistence level. It described Gould as an odd but essentially harmless drunk and obsessive. Gould died in 1957, and in 1964 Mitchell published his second article, "Joe Gould's Secret," which described the aftermath of the first article, and the effect it had on both Gould and Mitchell himself. Joe Gould was a Harvard graduate and an alcoholic Greenwich Village "street person," cadging drinks and handouts for decades, accepted locally as a colorful eccentric and bohemian. Gould's claim to fame was as a writer, having published some excerpts of his "An Oral History of Our Time," which Gould asserted consisted of thousands of pages, perhaps nine million written words, it was mission in life. He claimed it consisted of things he had seen or heard, half of it conversations taken down: "What people say is history," said Gould. Gould may not have been a myth, but he was more than a rumor. In the first New Yorker Profile, Mitchell accepted and publicized Gould's claims, which brought him both fame and a patron who provided Gould a minimal but comfortable standard of living. After Gould's death in 1957, his friends launched a search for the apparently scattered Oral History, but not much of the opus was located. In 1964, Mitchell published his second article, about five times as long as the first, in which he revealed his opinion that the Oral History never existed, except for a few specific topics that Gould had been obsessively rewriting (and ranting about) for years. Joe Gould's Secret is well written and compelling. If this book was fiction, there would be raves about the quirky, somewhat charming, and pitiful character, think A Fan's Notes or a Confederacy of Dunces. In the end, Gould may have been a conman who managed to maintain his alcoholic (and mentally ill) life through what was left of his wits. Mitchell was intrigued because he saw some of his own curious life in Gould's. Worth reading for the style of writing, insight into psychoses disguised as quirks, a vision of New York City gone by, myth-making, and certainly if planning on reading Jill Lepore's book. Unfortunately Lepore's book colored my reading of this, as it shows facets of Gould's character that Mitchell didn't know or didn't share. Lepore takes Mitchell's writings to the next level, both good and bad. By the same token, having read this now, my view of Lepore's Joe Gould's Teeth has changed, too. [4 Stars]

Book Review: Unfortunately, I read Jill Lepore's book Joe Gould's Teeth (2016) prior to reading Joe Gould's Secret by Joseph Mitchell. Actually, I read this because of Lepore's book, which was a response to Mitchell's articles. If you have the choice, read JG's Secret before reading JG's Teeth, and you'll have a better view of the whole picture here; in a better world, all three works would be reissued in a single volume. Joseph Mitchell wrote two New Yorker articles about Joe Gould. The first was "Professor Sea Gull," in 1942, which made Gould (at least locally) famous and enabled him to survive above a bare subsistence level. It described Gould as an odd but essentially harmless drunk and obsessive. Gould died in 1957, and in 1964 Mitchell published his second article, "Joe Gould's Secret," which described the aftermath of the first article, and the effect it had on both Gould and Mitchell himself. Joe Gould was a Harvard graduate and an alcoholic Greenwich Village "street person," cadging drinks and handouts for decades, accepted locally as a colorful eccentric and bohemian. Gould's claim to fame was as a writer, having published some excerpts of his "An Oral History of Our Time," which Gould asserted consisted of thousands of pages, perhaps nine million written words, it was mission in life. He claimed it consisted of things he had seen or heard, half of it conversations taken down: "What people say is history," said Gould. Gould may not have been a myth, but he was more than a rumor. In the first New Yorker Profile, Mitchell accepted and publicized Gould's claims, which brought him both fame and a patron who provided Gould a minimal but comfortable standard of living. After Gould's death in 1957, his friends launched a search for the apparently scattered Oral History, but not much of the opus was located. In 1964, Mitchell published his second article, about five times as long as the first, in which he revealed his opinion that the Oral History never existed, except for a few specific topics that Gould had been obsessively rewriting (and ranting about) for years. Joe Gould's Secret is well written and compelling. If this book was fiction, there would be raves about the quirky, somewhat charming, and pitiful character, think A Fan's Notes or a Confederacy of Dunces. In the end, Gould may have been a conman who managed to maintain his alcoholic (and mentally ill) life through what was left of his wits. Mitchell was intrigued because he saw some of his own curious life in Gould's. Worth reading for the style of writing, insight into psychoses disguised as quirks, a vision of New York City gone by, myth-making, and certainly if planning on reading Jill Lepore's book. Unfortunately Lepore's book colored my reading of this, as it shows facets of Gould's character that Mitchell didn't know or didn't share. Lepore takes Mitchell's writings to the next level, both good and bad. By the same token, having read this now, my view of Lepore's Joe Gould's Teeth has changed, too. [4 Stars]

Wednesday, August 3, 2016

Charlotte Bronte: A Fiery Heart by Claire Harman (2016)

A new biography of the author of Jane Eyre and Villette.

Book Review: The Brontes are the first family of literature, Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre are both classic novels, but I knew little of the three sisters, and much of what I knew was wrong. This has been corrected by the new biography, Charlotte Bronte: A Fiery Heart by Claire Harman (also the biographer of, inter alia, Sylvia Townsend Warner). I've not read any other biographies of the Bronte sisters, but this book is thoroughly researched and conversationally written. My image was of three parson's daughters stranded on the moors, writing passionate, Gothic novels whole cloth from fiery imaginations, dying unknown and tragically young. Little of that, except the last, was true. Although ostensibly this is a biography of Charlotte Bronte, her life was so intertwined with Emily and Anne that all three are well presented, which is what I was seeking. For me the first half of the book detailing their childhood and early writing efforts was slower, but the read really picked up upon publication of their poems and first novels, Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, and Agnes Grey. For others, the reaction might be quite the opposite as Harman provides a touching account of the extreme difficulties of growing up Bronte, and Charlotte's transformative but heartbreaking unrequited love for her professor in Brussels. Although the sisters used pseudonyms to hide their gender at publication, their books had both positive and negative receptions and the critical response, much of it sexist, classist, and misogynistic, continued for years. It's sad to see such criticism even today by readers who fail to appreciate this classic literature for such trivial reasons, considering what the authors endured in less enlightened times. Although I fully enjoyed Charlotte Bronte: A Fiery Heart, I'll mention two quibbles with Claire Harman, though both occurred rarely. First, she appears to take sides in some historical disputes, such as between Charlotte's father and her future husband, which shadows the purely objective facts. Certainly the weight of the evidence may lead to one conclusion or another, but the author shouldn't seem to be putting a subjective finger on the scales. Second, Harman seems to unnecessarily conjecture or interject her personal feelings, such as suggesting a reporter was "smitten," or intimating that only women long for a word from their love. But these minor points are rare, detract little from the narrative, and Harman is certainly not one of those pernicious but trendy biographers who feel their lives are of equal importance with their subject. Charlotte Bronte: A Fiery Heart is an excellent biography of Charlotte Bronte, and a good introduction to the lives and times of the whole Bronte family. I now want to read Anne, and more of Charlotte. [4 Stars]

Book Review: The Brontes are the first family of literature, Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre are both classic novels, but I knew little of the three sisters, and much of what I knew was wrong. This has been corrected by the new biography, Charlotte Bronte: A Fiery Heart by Claire Harman (also the biographer of, inter alia, Sylvia Townsend Warner). I've not read any other biographies of the Bronte sisters, but this book is thoroughly researched and conversationally written. My image was of three parson's daughters stranded on the moors, writing passionate, Gothic novels whole cloth from fiery imaginations, dying unknown and tragically young. Little of that, except the last, was true. Although ostensibly this is a biography of Charlotte Bronte, her life was so intertwined with Emily and Anne that all three are well presented, which is what I was seeking. For me the first half of the book detailing their childhood and early writing efforts was slower, but the read really picked up upon publication of their poems and first novels, Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, and Agnes Grey. For others, the reaction might be quite the opposite as Harman provides a touching account of the extreme difficulties of growing up Bronte, and Charlotte's transformative but heartbreaking unrequited love for her professor in Brussels. Although the sisters used pseudonyms to hide their gender at publication, their books had both positive and negative receptions and the critical response, much of it sexist, classist, and misogynistic, continued for years. It's sad to see such criticism even today by readers who fail to appreciate this classic literature for such trivial reasons, considering what the authors endured in less enlightened times. Although I fully enjoyed Charlotte Bronte: A Fiery Heart, I'll mention two quibbles with Claire Harman, though both occurred rarely. First, she appears to take sides in some historical disputes, such as between Charlotte's father and her future husband, which shadows the purely objective facts. Certainly the weight of the evidence may lead to one conclusion or another, but the author shouldn't seem to be putting a subjective finger on the scales. Second, Harman seems to unnecessarily conjecture or interject her personal feelings, such as suggesting a reporter was "smitten," or intimating that only women long for a word from their love. But these minor points are rare, detract little from the narrative, and Harman is certainly not one of those pernicious but trendy biographers who feel their lives are of equal importance with their subject. Charlotte Bronte: A Fiery Heart is an excellent biography of Charlotte Bronte, and a good introduction to the lives and times of the whole Bronte family. I now want to read Anne, and more of Charlotte. [4 Stars]

Monday, August 1, 2016

A Month of Murakami!

The Month of Murakami is over. It went pretty well, and I read seven of his books: Norwegian Wood (1987); Dance Dance Dance (1988); South of the Border, West of the Sun (1992); Sputnik Sweetheart (1999); After Dark (2004); The Strange Library (2005); and Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki (2013). I began but didn't complete Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World (1985)(still reading). That's a lot of Murakami! But I never hit overload or tired of reading him. The only thing inconvenient was the lack of flexibility and the unusual sense of being constrained in my reading. I like being able to pick up anything that looks good at the moment, but I buckled down and did my best to stick to the mission, and I learned a few things. First, I believe Haruki Murakami is a great writer and may win the Nobel some day. What also became clear is how much Murakami is a writer of emotions, willing to spend many pages delving into feelings, passions, relationships, and examining the mental state of his characters (which may seem a bit melodramatic to some). There are his consistent tropes: wells, ears, sex, mysterious women, jazz, whiskey, cats, loners, socially awkward men, classical music ... the list goes on: he would be a great author to write a dissertation about. Having previously read his first three books, Hear the Wind Sing (1979), Pinball 1973 (1980), and A Wild Sheep Chase (1982), I could really see his growth as writer up to Dance Dance Dance, where Murakami truly becomes Murakami and came into his own as an author. His novels also clearly divide into two worlds. The first contains the books that are generally first-person narrated love stories of a sort (such as his most famous, Norwegian Wood), in which the magic or supernatural is kept to a minimum. The other consists of the books that are much more fantastical (such as The Strange Library), with bizarre characters such as Colonel Sanders or Johnny Walker, and present abnormal events and alternate realities; some might call these magical realism but I'm unsure whether they fully fit the definition (in short, magical realism is when magical or fantastical events occur and are accepted in the mundane and everyday world). Most of the books I read this month fell into the first category, and the books I have left to read, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle (1994), Hard-Boiled Wonderland, 1Q84 (2009), and Kafka on the Shore (2002), fit into the second group. I'm not sure if that was intentional, but I guess that most Murakami fans prefer one over the other. And I'm still looking forward to, eventually, completing the books I have left.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)