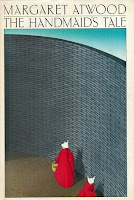

In a future America, religious extremists have imposed a theocracy in which fertile women have only one purpose.

Book Review: The Handmaid's Tale was begun in 1984, but even today finds resonance with readers. It's not SciFi, it is speculative fiction, just as is It Can't Happen Here by Sinclair Lewis. And like that book (and unlike most dystopian novels, which begin mid-tyranny) it describes the taking over of the commonplace American society by a tyrannical government, now renamed Gilead. Several pages in, the reader begins to suspect that this may be a secret book, perhaps not to be read by men. But perhaps not strictly feminist either, as so many female characters eagerly join in the tyranny of other women, our unnamed protagonist is no bold crusader (no Hunger Games or Divergent heroine here), and the Resistance appears well-populated by men. Interestingly, although Gilead is women-centered, it is not controlled by women. The ending of the book, though seemingly open-ended, is hopeful, and I liked it for that. The Handmaid's Tale is immensely thought-provoking; I might be able to write another 300 pages about this book. It's also a scary and valuable warning to be on our guard. When protectors of rights and liberties appear to overreact to threats, it's to avoid a future such as this. But heretical as it may be, there are places where this book is based heavily on our emotions, our fear of such a society, and as such some flaws appear. Logically, this is not the society that men would create given the chance (the implication in the book being that women had a say in creating the society). It also seems unbelievable that such a change, such a complete reorientation of thinking, could occur in such a short time. For instance, in just a few years the main character, a strong independent adult woman, loses much of her abilities, her personality, and periodically becomes feeble and ignorant. While this may be explicable (PTSD, shock, Stockholm syndrome, etc.) in terms of the story, it still felt unpersuasive given that at others times she does assert her strength (agency, for you lit majors). Further, the "Historical Notes" appended at the end were clunky, unnecessary, and distracting (much like the Harry Potter epilogue). It seemed as if Atwood didn't trust her reader, and the little valuable information there could have been better presented. Much of this is subjective, but I'll just mention one more. The underground railroad to Canada is called "The Underground Femaleroad." That just seems like a clunker to me, and I can't imagine anyone coming up with such a term. For me, none of these bumps undermined the power of the story or my enjoyment of it. The fairly minor flaws just kept it from being as perfect as I would have liked it to be, as it deserved to be. The Handmaid's Tale is soon to be a television series, is a (not well-reviewed) 1990 movie, and is well worth reading. [4★]

Thursday, March 30, 2017

Monday, March 27, 2017

Terrapin by Wendell Berry (2014)

A collection of wonderfully illustrated poems that children might like to read.

Poetry Review: Terrapin is a lovely collection of farmer/poet Wendell Berry's work, that illustrator Tom Pohrt thought that children might appreciate. The book contains 21 of Berry's simpler and shorter poems, but they have their own mysteries and can be well appreciated by adults, as well. Personally, I loved this book for its charming simplicity, and even by an adult it can be read over and over again for both the subtleties and the warm messages of the poems. No, this is not slam poetry, it's not edgy or dark, not hipster cool or ironic. The poems are un-ironic and sincere, a sincerity that you can read and love in the privacy of your own bedroom. Go ahead, be daring, read as a child, with a child's eyes, and heart, as you did when you were a child. Be that better you from long ago. Here is one:

The first man who whistled

thought he had a wren in his mouth.

He went around all day

with his lips puckered,

afraid to swallow.

The poems are heavy on nature, animals, and life on Berry's farm. There are poems about horses, snakes, squirrels, a calf, and finches; poems about planting trees, the seasons, and sleep. And then there is the title poem, which I think (surprise!) is the most wonderful of all the poems in Terrapin. Childlike, not childish, and any child would love it. The illustrations are all well worth examining for their own sake. The pictures are warm, sweet, adorable, and maybe one or two are even a little cheesy, in a good way, like a good friend who tells bad jokes. It's hard to tell if the paintings illustrate the poems or the poems capture the pictures. This book would be a perfect gift (hardback or paperback) for any occasion. Perfect for a young child who likes to be read to, or an older child who has started to read. Or, as with me, an adult of any age. I don't know if children will understand all the poems in Terrapin, or even all the words, but it will be wonderful for them to try. [4★]

Poetry Review: Terrapin is a lovely collection of farmer/poet Wendell Berry's work, that illustrator Tom Pohrt thought that children might appreciate. The book contains 21 of Berry's simpler and shorter poems, but they have their own mysteries and can be well appreciated by adults, as well. Personally, I loved this book for its charming simplicity, and even by an adult it can be read over and over again for both the subtleties and the warm messages of the poems. No, this is not slam poetry, it's not edgy or dark, not hipster cool or ironic. The poems are un-ironic and sincere, a sincerity that you can read and love in the privacy of your own bedroom. Go ahead, be daring, read as a child, with a child's eyes, and heart, as you did when you were a child. Be that better you from long ago. Here is one:

The first man who whistled

thought he had a wren in his mouth.

He went around all day

with his lips puckered,

afraid to swallow.

The poems are heavy on nature, animals, and life on Berry's farm. There are poems about horses, snakes, squirrels, a calf, and finches; poems about planting trees, the seasons, and sleep. And then there is the title poem, which I think (surprise!) is the most wonderful of all the poems in Terrapin. Childlike, not childish, and any child would love it. The illustrations are all well worth examining for their own sake. The pictures are warm, sweet, adorable, and maybe one or two are even a little cheesy, in a good way, like a good friend who tells bad jokes. It's hard to tell if the paintings illustrate the poems or the poems capture the pictures. This book would be a perfect gift (hardback or paperback) for any occasion. Perfect for a young child who likes to be read to, or an older child who has started to read. Or, as with me, an adult of any age. I don't know if children will understand all the poems in Terrapin, or even all the words, but it will be wonderful for them to try. [4★]

Friday, March 24, 2017

The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin (1974)

A visitor from a bare subsistence moon colony returns to the home planet to try to reunite the two civilizations.

Book Review: The Dispossessed lovingly sinks deeper into layers of meaning, providing more sustenance as the chapters go by. Since Le Guin belongs to the canon of great SciFi writers, the reader knows that this is not going to be the simple tale it seems at first. She's built two worlds, one an anarchist, communal society (think maybe something like Abnegation from Divergent) that barely survives in its inhospitable climate, having only the barest contact with the other world, its home planet, which is a paraphrase and extrapolation of Earth, circa 1975. The Dispossessed is told through two timelines in alternating chapters, appropriate when the main character is a temporal physicist. One timeline looks at the 170 year history of the communal society through the main character, the other looks at the home planet with its great competing countries like the great competing countries of today. Le Guin is determined to write a serious book, a novel of ideas, discussing socio-economic-political concerns through the plot (it won both the Hugo and the Nebula awards). As a result it can a bit talky, or even quite talky in spots. But the reader cares, not because it's so important to the reader, but because it's so important to Le Guin, and we like her characters. One of her strong points is that nothing is ever black and white, only infinite shades of gray. There is no cloying perfection. Although it's clear where her biases lie, she shows strengths and flaws in all the systems presented, and in all the characters. Politically committed readers will have their beliefs tweaked. The Dispossessed is not a speedy read, heavier on ideas and character development than plot, but it's always intriguing and makes the reader think, even if it's light on the thrills; for some the ending will be underwhelming. The novel is part of Le Guin's Hainish cycle of books. [4★]

Book Review: The Dispossessed lovingly sinks deeper into layers of meaning, providing more sustenance as the chapters go by. Since Le Guin belongs to the canon of great SciFi writers, the reader knows that this is not going to be the simple tale it seems at first. She's built two worlds, one an anarchist, communal society (think maybe something like Abnegation from Divergent) that barely survives in its inhospitable climate, having only the barest contact with the other world, its home planet, which is a paraphrase and extrapolation of Earth, circa 1975. The Dispossessed is told through two timelines in alternating chapters, appropriate when the main character is a temporal physicist. One timeline looks at the 170 year history of the communal society through the main character, the other looks at the home planet with its great competing countries like the great competing countries of today. Le Guin is determined to write a serious book, a novel of ideas, discussing socio-economic-political concerns through the plot (it won both the Hugo and the Nebula awards). As a result it can a bit talky, or even quite talky in spots. But the reader cares, not because it's so important to the reader, but because it's so important to Le Guin, and we like her characters. One of her strong points is that nothing is ever black and white, only infinite shades of gray. There is no cloying perfection. Although it's clear where her biases lie, she shows strengths and flaws in all the systems presented, and in all the characters. Politically committed readers will have their beliefs tweaked. The Dispossessed is not a speedy read, heavier on ideas and character development than plot, but it's always intriguing and makes the reader think, even if it's light on the thrills; for some the ending will be underwhelming. The novel is part of Le Guin's Hainish cycle of books. [4★]

Monday, March 20, 2017

Agnes Grey by Anne Bronte (1847)

A young woman becomes a governess, meeting the world, the wealthy, and woo.

Book Review: Agnes Grey is Anne Bronte's first novel, and reminds me less of her sisters' books and more of Jane Austen. Agnes seems to share much with the good Fanny Price from Mansfield Park. How much the reader loves this book will depend on how closely one identifies with Agnes: if the reader values steadfast virtue, granite conviction, and religious zeal she will most likely love it. The novel is well written, enjoyable, a nice if not too exciting story, and a quick read (it's short). But for me, Agnes the young governess is just a little too judgmental and self-righteous. According to Agnes, not a single member of her employers' families, their staff, or friends is a decent human being. Sure, one of the children of the first family she works for is an incipient serial killer, which causes Agnes to commit a mercy killing. But she describes the adults in the first family she works for as "cold, grave, and forbidding," "hypocritical and insincere," "peevish," and worse; the children are described as "shocking," "wicked," "violent," "perverse," "incorrigible," and more. Teaching them is a Herculean ordeal, especially as Agnes is young and has no training as a governess. Moving on to her second employers, the father is a man given to "swearing and blaspheming," and the children are (in short) "insolent and overbearing" and "wrong-headed," including a young daughter who could "swear like a trooper." The entire family has a "sad want of principle" and are compared to "a race of intractable savages." Agnes' judgmental eye jabs all she meets, such as "military fops." She herself does not take criticism well. Perhaps the wealthy English were so extremely horrid at the time (entirely possible, especially in their treatment of a young governess), but as Agnes says at one point: "Had I seen it depicted in a novel I should have thought it unnatural." She does have an occasional surprise dash of humor, but sadly acknowledges that she can have no friends or acquaintances in her situation. Of her closest friend in the family she says, "There are, I suppose, some men as vain, as selfish, and as heartless as she is, and perhaps such women may be useful to punish them." Ouch.

All of this is in service to one of the themes of Agnes Gray: the wealthy look down on Agnes because she's lower class, Agnes looks down on the wealthy because of their weak virtue. Obviously Agnes' side has the better of it, but then again, Agnes tells the story. As we know from other Victorian novels, governesses of the time were in an awkward position: above the servants and not a servant, but decidedly beneath her employers in status. But Agnes perseveres, she endures, she lasts.

The romance is sweet, if predictable, and causes Agnes some distress when she realizes she visits the needy in hopes of seeing her crush, goes to church to see him, and perhaps loves him more than her religion. Having been fairly sure of her convictions all along, she finally begins to have doubts about her righteousness, and even her looks and temperament: "consider your own unattractive exterior, your unamiable reserve, your foolish diffidence, which must make you appear cold, dull, awkward, and perhaps ill-tempered too." Although this self-doubt regards her love, I like to think she finally has grown to realize that some of her problems all along were of her own making. Perhaps Agnes has grown a little during her long struggle with rotten children and their unsupportive parents (good thing she never taught middle school). Agnes Grey is an easy and enjoyable read, and necessary if you want to know all the Brontes, as I do. The key litmus test of the novel is the reader's take on Agnes herself. I'll close with my favorite line from the book: "You can't expect a cat to know manners like a Christian." [3★]

Book Review: Agnes Grey is Anne Bronte's first novel, and reminds me less of her sisters' books and more of Jane Austen. Agnes seems to share much with the good Fanny Price from Mansfield Park. How much the reader loves this book will depend on how closely one identifies with Agnes: if the reader values steadfast virtue, granite conviction, and religious zeal she will most likely love it. The novel is well written, enjoyable, a nice if not too exciting story, and a quick read (it's short). But for me, Agnes the young governess is just a little too judgmental and self-righteous. According to Agnes, not a single member of her employers' families, their staff, or friends is a decent human being. Sure, one of the children of the first family she works for is an incipient serial killer, which causes Agnes to commit a mercy killing. But she describes the adults in the first family she works for as "cold, grave, and forbidding," "hypocritical and insincere," "peevish," and worse; the children are described as "shocking," "wicked," "violent," "perverse," "incorrigible," and more. Teaching them is a Herculean ordeal, especially as Agnes is young and has no training as a governess. Moving on to her second employers, the father is a man given to "swearing and blaspheming," and the children are (in short) "insolent and overbearing" and "wrong-headed," including a young daughter who could "swear like a trooper." The entire family has a "sad want of principle" and are compared to "a race of intractable savages." Agnes' judgmental eye jabs all she meets, such as "military fops." She herself does not take criticism well. Perhaps the wealthy English were so extremely horrid at the time (entirely possible, especially in their treatment of a young governess), but as Agnes says at one point: "Had I seen it depicted in a novel I should have thought it unnatural." She does have an occasional surprise dash of humor, but sadly acknowledges that she can have no friends or acquaintances in her situation. Of her closest friend in the family she says, "There are, I suppose, some men as vain, as selfish, and as heartless as she is, and perhaps such women may be useful to punish them." Ouch.

All of this is in service to one of the themes of Agnes Gray: the wealthy look down on Agnes because she's lower class, Agnes looks down on the wealthy because of their weak virtue. Obviously Agnes' side has the better of it, but then again, Agnes tells the story. As we know from other Victorian novels, governesses of the time were in an awkward position: above the servants and not a servant, but decidedly beneath her employers in status. But Agnes perseveres, she endures, she lasts.

The romance is sweet, if predictable, and causes Agnes some distress when she realizes she visits the needy in hopes of seeing her crush, goes to church to see him, and perhaps loves him more than her religion. Having been fairly sure of her convictions all along, she finally begins to have doubts about her righteousness, and even her looks and temperament: "consider your own unattractive exterior, your unamiable reserve, your foolish diffidence, which must make you appear cold, dull, awkward, and perhaps ill-tempered too." Although this self-doubt regards her love, I like to think she finally has grown to realize that some of her problems all along were of her own making. Perhaps Agnes has grown a little during her long struggle with rotten children and their unsupportive parents (good thing she never taught middle school). Agnes Grey is an easy and enjoyable read, and necessary if you want to know all the Brontes, as I do. The key litmus test of the novel is the reader's take on Agnes herself. I'll close with my favorite line from the book: "You can't expect a cat to know manners like a Christian." [3★]

Wednesday, March 15, 2017

A Kiss Before Dying by Ira Levin (1953)

A single-minded narcissist is a dangerous thing (the first novel by the author of Rosemary's Baby and The Stepford Wives).

Book Review: A Kiss Before Dying is an excellent mystery thriller. Beyond that there's not much more to say. The book is so cleverly put together that it's virtually seamless, the reader just goes along for the ride and the last 50 pages or so go by in a blur. It's like one of those wooden puzzle boxes that you can't figure out how it works or watching someone do a Rubik's Cube. It just happens. There are even a few fun and vertigo-inducing twists where the reader wonders "where am I?" For those familiar with modern mystery thrillers, A Kiss Before Dying may seem a little less shocking or sensational, a fraction slower and deliberately paced, and perhaps just a wee bit predictable. In 1953 it would have been even more powerful, with its main character who just wants to impress his mother. But A Kiss Before Dying is quick, enjoyable read, rewarding and entertaining, and made me want to read more by the not-too-prolific Ira Levin. Filmed twice, in 1956 and 1991. [4★]

Book Review: A Kiss Before Dying is an excellent mystery thriller. Beyond that there's not much more to say. The book is so cleverly put together that it's virtually seamless, the reader just goes along for the ride and the last 50 pages or so go by in a blur. It's like one of those wooden puzzle boxes that you can't figure out how it works or watching someone do a Rubik's Cube. It just happens. There are even a few fun and vertigo-inducing twists where the reader wonders "where am I?" For those familiar with modern mystery thrillers, A Kiss Before Dying may seem a little less shocking or sensational, a fraction slower and deliberately paced, and perhaps just a wee bit predictable. In 1953 it would have been even more powerful, with its main character who just wants to impress his mother. But A Kiss Before Dying is quick, enjoyable read, rewarding and entertaining, and made me want to read more by the not-too-prolific Ira Levin. Filmed twice, in 1956 and 1991. [4★]

Monday, March 13, 2017

The Man in the Queue by Josephine Tey (1929)

Inspector Grant is assigned a case involving the fatal stabbing of an unknown man in a theater queue.

Book Review: The Man in the Queue is the first Inspector Grant novel by Scottish author Elizabeth MacKintosh, originally published under the pseudonym Gordon Daviot (which she used mostly for her plays), then later under her better-known pseudonym Josephine Tey, to bring it in line with the five later Inspector Grant mysteries. This is uniquely written mystery. It is slowly paced, as the reader feels no terrible urgency to read faster, but plods along with Inspector Grant, as he puzzles out every possible thread, happily ignoring certain clues. At points the reader is certain that Grant is following a red herring, at others the reader demands that the Inspector go down another path. But Grant just seemingly bobbles along, taking his time, thinking everything through in exquisite detail. Grant believes, and the reader may agree, that he has too much imagination for a policeman. Just a warning: this is not a whodunnit, you will not figure out the surprise ending. If anything it's a procedural, as we witness the good Inspector deliberately rolling along to the conclusion. The Man in the Queue is also enjoyable as a kind of time machine, taking us back to 1920s England. I was intrigued to see stereotypes and assumptions about gender and ethnicity so casually made, reflecting the tenor of the times. Our intrepid detectives easily assume, a woman couldn't've done this, an Englishman would've done that, a man must've done the other, a Scot does something else, and only a Levantine (!) could've done this. What a way to solve a case. At one point there's a discussion "whether a mixture of race in a person is a good thing," not "black and white, but different stocks of white." Later, Grant thinks that one individual "had all a red-haired person's shrewdness and capability." Really? Who knew! Only the boldest and most unconventional authors would dare have their characters make such statements today. But in Tey's hands it all seems harmless, almost quaint, even as it's clearly noticeable and notable. The Man in the Queue was followed by the second Inspector Grant mystery, A Shilling for Candles, in 1936. This one was an enjoyable mystery story, which proceeds at its own deliberate pace, and leaves the reader with a spoonful of marmite at the end. [3½★]

Book Review: The Man in the Queue is the first Inspector Grant novel by Scottish author Elizabeth MacKintosh, originally published under the pseudonym Gordon Daviot (which she used mostly for her plays), then later under her better-known pseudonym Josephine Tey, to bring it in line with the five later Inspector Grant mysteries. This is uniquely written mystery. It is slowly paced, as the reader feels no terrible urgency to read faster, but plods along with Inspector Grant, as he puzzles out every possible thread, happily ignoring certain clues. At points the reader is certain that Grant is following a red herring, at others the reader demands that the Inspector go down another path. But Grant just seemingly bobbles along, taking his time, thinking everything through in exquisite detail. Grant believes, and the reader may agree, that he has too much imagination for a policeman. Just a warning: this is not a whodunnit, you will not figure out the surprise ending. If anything it's a procedural, as we witness the good Inspector deliberately rolling along to the conclusion. The Man in the Queue is also enjoyable as a kind of time machine, taking us back to 1920s England. I was intrigued to see stereotypes and assumptions about gender and ethnicity so casually made, reflecting the tenor of the times. Our intrepid detectives easily assume, a woman couldn't've done this, an Englishman would've done that, a man must've done the other, a Scot does something else, and only a Levantine (!) could've done this. What a way to solve a case. At one point there's a discussion "whether a mixture of race in a person is a good thing," not "black and white, but different stocks of white." Later, Grant thinks that one individual "had all a red-haired person's shrewdness and capability." Really? Who knew! Only the boldest and most unconventional authors would dare have their characters make such statements today. But in Tey's hands it all seems harmless, almost quaint, even as it's clearly noticeable and notable. The Man in the Queue was followed by the second Inspector Grant mystery, A Shilling for Candles, in 1936. This one was an enjoyable mystery story, which proceeds at its own deliberate pace, and leaves the reader with a spoonful of marmite at the end. [3½★]

Friday, March 10, 2017

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro (1989)

The butler for an aristocratic English family travels through the countryside, reflecting on service, family, the modern age, love not loved and a life not lived.

Book Review: The Remains of the Day is perhaps a perfect book. Certainly the most perfectly written book I've ever read. Ishiguro controls the tone, pacing, substance, everything as well as it's ever been done. Never a break in the presentation, nothing to throw the reader out of the story, never a misstep. At the same time, everything is extremely subtle and quiet, with only the rare overt action. A very adult book, in the sense of being able to reflect and appreciate. All emotion is strictly controlled. If you want excitement and car chases you won't find it in The Remains of the Day. Even a raised voice or unpleasant tone of voice is uncommon and shocking. The whole of the plot exists deep under the surface, with the characters' thoughts carrying the action. It's like a painting with only minimal shifts in color and tint. You have to look close to see the composition. This is the muffled crack of a twig in the forest, not an elk crashing through the trees. Few shocks or surprises, except in the readers' slow realization as to what is happening beneath the surface. Yet the characters' emotions were powerful, I was embarrassed for them, felt their desperation, regretted with them. The Remains of the Day is a quiet book, but with all rage and yearning buried deep. I wouldn't say it's the best book ever written, but the most perfectly written book. A masterpiece, a tour de force. [5★]

Book Review: The Remains of the Day is perhaps a perfect book. Certainly the most perfectly written book I've ever read. Ishiguro controls the tone, pacing, substance, everything as well as it's ever been done. Never a break in the presentation, nothing to throw the reader out of the story, never a misstep. At the same time, everything is extremely subtle and quiet, with only the rare overt action. A very adult book, in the sense of being able to reflect and appreciate. All emotion is strictly controlled. If you want excitement and car chases you won't find it in The Remains of the Day. Even a raised voice or unpleasant tone of voice is uncommon and shocking. The whole of the plot exists deep under the surface, with the characters' thoughts carrying the action. It's like a painting with only minimal shifts in color and tint. You have to look close to see the composition. This is the muffled crack of a twig in the forest, not an elk crashing through the trees. Few shocks or surprises, except in the readers' slow realization as to what is happening beneath the surface. Yet the characters' emotions were powerful, I was embarrassed for them, felt their desperation, regretted with them. The Remains of the Day is a quiet book, but with all rage and yearning buried deep. I wouldn't say it's the best book ever written, but the most perfectly written book. A masterpiece, a tour de force. [5★]

Wednesday, March 8, 2017

The High Crusade by Poul Anderson (1960)

Lincolnshire, in the East Midlands of England, the year 1345, war with France imminent, when a huge cylinder over 2000 feet long, all of metal, lands in the village of Ansby.

Book Review: The High Crusade is good fun, an adventure story, moderately frivolous science fiction, a blast from the (distant) past. Poul Anderson has done the research to create the requisite verisimilitude and sets a reasonable pace in telling the unlikely tale contained in this short novel. There's even a smattering of romance thrown in for a subplot. Twists and turns aplenty. If the reader wants more than the light entertainment promised and delivered, The High Crusade can be read as a fine example of the typical American sci-fi novel of its time. Although the constant refrain throughout is of the unconquerable fortitude of Englishmen, the tale is actually emblematic of the 1950's American "can-do" attitude, that any challenge can be overcome with technology and frontier spirit. Cloaking this mid-century trope in olde Englishisms makes it even more palatable and enjoyable. Adding additional levels of scrutiny is more weight than this slender reed of a novel can bear, but it's easily susceptible to historicism and post-colonial study for those of a more serious bent. I ain't gonna go there. In short, The High Crusade is a fun quick read with more surprises than expected (which is the purpose of surprises, right?). [3.5★]

Book Review: The High Crusade is good fun, an adventure story, moderately frivolous science fiction, a blast from the (distant) past. Poul Anderson has done the research to create the requisite verisimilitude and sets a reasonable pace in telling the unlikely tale contained in this short novel. There's even a smattering of romance thrown in for a subplot. Twists and turns aplenty. If the reader wants more than the light entertainment promised and delivered, The High Crusade can be read as a fine example of the typical American sci-fi novel of its time. Although the constant refrain throughout is of the unconquerable fortitude of Englishmen, the tale is actually emblematic of the 1950's American "can-do" attitude, that any challenge can be overcome with technology and frontier spirit. Cloaking this mid-century trope in olde Englishisms makes it even more palatable and enjoyable. Adding additional levels of scrutiny is more weight than this slender reed of a novel can bear, but it's easily susceptible to historicism and post-colonial study for those of a more serious bent. I ain't gonna go there. In short, The High Crusade is a fun quick read with more surprises than expected (which is the purpose of surprises, right?). [3.5★]

Monday, March 6, 2017

It Can't Happen Here by Sinclair Lewis (1935)

What if an egomaniacal narcissist and sociopath posing as a populist was elected President of the United States?

Book Review: It Can't Happen Here is being read by everybody, their sister, and their aunt's cat these days. Why? The book has been dismissed as "not much of a novel." I'd say that Naked Lunch isn't much of a novel, but the real question is what the author was trying to do with a novel. If the author's goal was to create a warning wrapped inside a work of propaganda, then It Can't Happen Here is a brilliant novel. Sinclair Lewis asks what if in the midst of the Great Depression Roosevelt didn't get a second term in 1936, outmaneuvered by a power hungry politician with delusions of grandeur (perhaps modeled on Huey Long, but with modern comparisons also). In the book Lewis skewers both fascists and communists alike, and creates a reasonable portrayal of America becoming like the contemporary European fascist countries. At the time there were genuine threats to the American government from both the right and left, and this book shows how in reality Roosevelt saved America from extremism. But I have to admit that I read it with only half my attention, as the other half was distracted by the novel's similarities to what's going on in the political world today. Some similarities are minor and purely coincidental, but other parallels are disturbing. There are too many parallels to mention them all, but this fictional president cozies up to murderous foreign dictators, has an evil genius behind his actions, anticipates vast business dealings with the Russians, believes the media spreads "lies," tries to control the news, makes populist promises that are never fulfilled, caters to the large corporations, is misogynist (women are limited to working in beauty parlors and nursing), racist, and anti-semitic, sees Americans fleeing to Canada ... and many more, eventually I stopped keeping track. Oddly, the President's wife stays home and sees her husband once a week, his book is ghost-written, his administration takes well into February to get organized, he deceitfully inflates the reports of the crowds that come to see him, and more and more. It Can't Happen Here is entertaining, as much for its relation to current events as for the historical events of the time, and well worth reading as both a civics lesson and a warning that America's greatest danger is within. [4★]

Book Review: It Can't Happen Here is being read by everybody, their sister, and their aunt's cat these days. Why? The book has been dismissed as "not much of a novel." I'd say that Naked Lunch isn't much of a novel, but the real question is what the author was trying to do with a novel. If the author's goal was to create a warning wrapped inside a work of propaganda, then It Can't Happen Here is a brilliant novel. Sinclair Lewis asks what if in the midst of the Great Depression Roosevelt didn't get a second term in 1936, outmaneuvered by a power hungry politician with delusions of grandeur (perhaps modeled on Huey Long, but with modern comparisons also). In the book Lewis skewers both fascists and communists alike, and creates a reasonable portrayal of America becoming like the contemporary European fascist countries. At the time there were genuine threats to the American government from both the right and left, and this book shows how in reality Roosevelt saved America from extremism. But I have to admit that I read it with only half my attention, as the other half was distracted by the novel's similarities to what's going on in the political world today. Some similarities are minor and purely coincidental, but other parallels are disturbing. There are too many parallels to mention them all, but this fictional president cozies up to murderous foreign dictators, has an evil genius behind his actions, anticipates vast business dealings with the Russians, believes the media spreads "lies," tries to control the news, makes populist promises that are never fulfilled, caters to the large corporations, is misogynist (women are limited to working in beauty parlors and nursing), racist, and anti-semitic, sees Americans fleeing to Canada ... and many more, eventually I stopped keeping track. Oddly, the President's wife stays home and sees her husband once a week, his book is ghost-written, his administration takes well into February to get organized, he deceitfully inflates the reports of the crowds that come to see him, and more and more. It Can't Happen Here is entertaining, as much for its relation to current events as for the historical events of the time, and well worth reading as both a civics lesson and a warning that America's greatest danger is within. [4★]

Wednesday, March 1, 2017

Autumn by Ali Smith (2016)

An old man and a young girl who love each other, grow together and separately through turbulent times in England.

Book review: Autumn was my introduction to Ali Smith, and a quite positive introduction at that. The main character is a junior art lecturer in London, and art is an integral part of the book. As such, Smith's writing can be likened to Cubism as it shows various sides of issues and life at the same time; to collage as it patches together separate, disparate bits to create a whole; to simple sketches as the entire piece is never given in depth; but I prefer to think of it as pointillism as she gives us numerous points of light, generously mixing time and memory, to create her novel. If I can't use art as metaphor, than Woolf is the author the reader is most likely to draw to mind. The main time line occurs shortly after Brexit, but Smith also brings in the Profumo/Keeler affair and other real world moments. Our main character, Elisabeth, whose surname is the none too subtle "Demand," confronts the world, bureaucracy in particular, only on her own terms regardless of who she hurts, including herself (the fairy tale Goldilocks is described as a "bad wicked rude vandal of a girl"). She has a wonderful, loving, life-long friendship with Daniel, a man 69 years her senior, which forms the central relationship of Autumn. What is particularly valuable about the relationship is that the two are just people, ungendered, and it doesn't matter that Elisabeth is female or Daniel is male (and gay). The relationship doesn't carry the typical fictional baggage of a friendship between two women, two men, or a woman and a man. The two are free to be just themselves, just richly and delightfully human -- which leads to the telling moment of the book. Smith doesn't go deeply into the characters, but her subtle writing suggests depths for readers to find on their own. Autumn was an enjoyable, quick read. Although Smith plays with time at will, jumbling up lives and history, she always provides helpful signposts so the reader is never misplaced beyond a line or two. There are serious moments and issues raised, but generally the tone is light, fresh, and warm, with only hints of darker times. She puns, she talks about story telling, it seems that Smith enjoyed herself writing this, and though probably untrue, it feels that it was written in a heartbeat, dashed off in a moment. The book is also a love letter to the talented and beautiful Pauline Boty, real-life 60s London Pop artist who died young and who Smith wants us to remember. Finally, what is also striking is how much of Ali Smith's spot on description of Britain after the referendum ("It is the end of dialogue") is also a spot on description of the States after the presidential election. After reading Autumn, I certainly want to read more by Ali Smith. [4★]

Book review: Autumn was my introduction to Ali Smith, and a quite positive introduction at that. The main character is a junior art lecturer in London, and art is an integral part of the book. As such, Smith's writing can be likened to Cubism as it shows various sides of issues and life at the same time; to collage as it patches together separate, disparate bits to create a whole; to simple sketches as the entire piece is never given in depth; but I prefer to think of it as pointillism as she gives us numerous points of light, generously mixing time and memory, to create her novel. If I can't use art as metaphor, than Woolf is the author the reader is most likely to draw to mind. The main time line occurs shortly after Brexit, but Smith also brings in the Profumo/Keeler affair and other real world moments. Our main character, Elisabeth, whose surname is the none too subtle "Demand," confronts the world, bureaucracy in particular, only on her own terms regardless of who she hurts, including herself (the fairy tale Goldilocks is described as a "bad wicked rude vandal of a girl"). She has a wonderful, loving, life-long friendship with Daniel, a man 69 years her senior, which forms the central relationship of Autumn. What is particularly valuable about the relationship is that the two are just people, ungendered, and it doesn't matter that Elisabeth is female or Daniel is male (and gay). The relationship doesn't carry the typical fictional baggage of a friendship between two women, two men, or a woman and a man. The two are free to be just themselves, just richly and delightfully human -- which leads to the telling moment of the book. Smith doesn't go deeply into the characters, but her subtle writing suggests depths for readers to find on their own. Autumn was an enjoyable, quick read. Although Smith plays with time at will, jumbling up lives and history, she always provides helpful signposts so the reader is never misplaced beyond a line or two. There are serious moments and issues raised, but generally the tone is light, fresh, and warm, with only hints of darker times. She puns, she talks about story telling, it seems that Smith enjoyed herself writing this, and though probably untrue, it feels that it was written in a heartbeat, dashed off in a moment. The book is also a love letter to the talented and beautiful Pauline Boty, real-life 60s London Pop artist who died young and who Smith wants us to remember. Finally, what is also striking is how much of Ali Smith's spot on description of Britain after the referendum ("It is the end of dialogue") is also a spot on description of the States after the presidential election. After reading Autumn, I certainly want to read more by Ali Smith. [4★]

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)