Charles Bukowski's fictional memoir of growing up and discovering D.H. Lawrence.

Book Review: If you're thinking of reading Charles Bukowski, undoubtedly begin with Ham on Rye. Any discussion or opinion of Bukowski is worthless without having read this book. Bukowski fans must read this story of Henry Chinaski's early life (from birth to age 21), and non-Bukowski fans should find more here than in any of his other novels. Reading Ham on Rye will give readers much greater insight into his other writing and his messed-up life. This is the best of Bukowski's books, he seems to have worked harder on this one than his others, and although most all his books seem at least semi-autobiographical, Ham on Rye comes closest to an actual memoir, and a painful, ugly, gritty, slab of reality it is. Chinaski's father is an angry, bitter, violent, and brutal failure (who hates drunks). The villain of the story, he sets impossible standards for Henry, continually mocks him, and beats him relentlessly. Like so many, he escapes into reading. Ham on Rye is filled with the pitiable epiphanies of Henry's life. When in the fifth grade he finds that he can write well: "So that's what they wanted: lies. Beautiful lies." In junior high he drinks for the first time and realizes, "I have found something that is going to help me, for a long, long time to come." He suffers such an extreme form of acne and boils on his face and body that he is unable to attend school, and is physically and emotionally scarred for life. He lives through the poverty of the Great Depression, at times with both his parents out of work, and sees how the system treats those at the bottom: "They experimented on the poor and if that worked they used the treatment on the rich. And if it didn't work, there would still be more poor left over to experiment upon." Of course he also discovers women and sex, although there is little he can do about it at the time. One of Henry's recurring traits is his ability to sabotage himself in everything he does. Ham on Rye ends with the bombing of Pearl Harbor, and a friend going off to war. Bukowski's novel Factotum follows chronologically in the epic quest that is the life of Henry Chinaski, and is an excellent choice to read next. And for just a moment of speculation: I don't know if anyone has thought of this, but my guess is the book's title (it's not explained in the novel) comes from Catcher in the Rye. Bukowski is saying, "I'm not a catcher in the rye (if you recall that image from Salinger), I'm just a ham on rye, basic as it gets. Ham on Rye is about more than Chinaski's dog-eat-dog life, it's about economics, it's about America during a certain time in history, about people in all their desperate masks. Unexpectedly for me, there is some beautiful writing here. Despite the occasional moments of beauty, to see the underbelly of the American Dream, read Ham on Rye. [5 Stars]

Friday, July 29, 2016

Wednesday, July 27, 2016

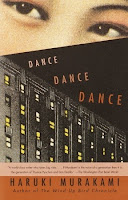

Dance Dance Dance by Haruki Murakami (1988)

A middle-aged man searches for the source of the weeping, the calling, he hears deep in his mind, and then tries to find a connection between the varied people he meets along the way.

Book Review: Dance Dance Dance is the fourth book (following A Wild Sheep Chase) in the "Rat Trilogy" (yep, I know, but it's Haruki Murakami after all -- I wonder if at one time he was thinking of having all his novels have the same narrator, and even this book doesn't fully resolve so the narrative could have continued ...). I should note that even tho this is the fourth book in the "Rat" series, both Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World and Norwegian Wood were published between A Wild Sheep Chase and this novel (making it his sixth novel). Reading the first three books isn't necessary as this book can stand alone, but I think it fits in quite well after the first three and a number of characters and incidents stem from A Wild Sheep Chase (tho with inconsistencies as well); your reading experience will be better, if for nothing else but to see the author's incredible growth as a writer over these books. Here Murakami is the Murakami we know and love. There is magic, a Sheep Man, call girls, a lost love, a famous actor, a young psychic girl, the ghost of an old hotel. There's an author named Hiraku Makimura (why does that name seem so familiar?). Dance Dance Dance is almost a picaresque novel, but instead of encountering a series of adventures our hero encounters a series of people of varied reality, and tries to decipher the links that bind those he meets (there's even a handy chart provided). This book meanders almost as if even Murakami wasn't sure what was coming next, but somehow it works and the story carries both protagonist and reader along on the quest. This isn't edge-of-your-seat reading, more of a calm intellectual and emotional search for the meaning in life. At one point a character comments: "I used to think ... that you get older one year at a time ... but it's not like that. It happens overnight." Dance Dance Dance starts with "It doesn't matter whether you like it or not -- a job's a job," and ends with "maybe, it was time to ... do some writing for myself ... not a novel or anything. But something for myself." The translation (by Alfred Birnbaum) is competent, if not inspiring. Dance Dance Dance quietly drew me into the mystery and kept me reading to the end of the journey. [4 Stars]

Book Review: Dance Dance Dance is the fourth book (following A Wild Sheep Chase) in the "Rat Trilogy" (yep, I know, but it's Haruki Murakami after all -- I wonder if at one time he was thinking of having all his novels have the same narrator, and even this book doesn't fully resolve so the narrative could have continued ...). I should note that even tho this is the fourth book in the "Rat" series, both Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World and Norwegian Wood were published between A Wild Sheep Chase and this novel (making it his sixth novel). Reading the first three books isn't necessary as this book can stand alone, but I think it fits in quite well after the first three and a number of characters and incidents stem from A Wild Sheep Chase (tho with inconsistencies as well); your reading experience will be better, if for nothing else but to see the author's incredible growth as a writer over these books. Here Murakami is the Murakami we know and love. There is magic, a Sheep Man, call girls, a lost love, a famous actor, a young psychic girl, the ghost of an old hotel. There's an author named Hiraku Makimura (why does that name seem so familiar?). Dance Dance Dance is almost a picaresque novel, but instead of encountering a series of adventures our hero encounters a series of people of varied reality, and tries to decipher the links that bind those he meets (there's even a handy chart provided). This book meanders almost as if even Murakami wasn't sure what was coming next, but somehow it works and the story carries both protagonist and reader along on the quest. This isn't edge-of-your-seat reading, more of a calm intellectual and emotional search for the meaning in life. At one point a character comments: "I used to think ... that you get older one year at a time ... but it's not like that. It happens overnight." Dance Dance Dance starts with "It doesn't matter whether you like it or not -- a job's a job," and ends with "maybe, it was time to ... do some writing for myself ... not a novel or anything. But something for myself." The translation (by Alfred Birnbaum) is competent, if not inspiring. Dance Dance Dance quietly drew me into the mystery and kept me reading to the end of the journey. [4 Stars]

Monday, July 25, 2016

Sixpence House: Lost in a Town of Books by Paul Collins (2003)

An American writer and his family move to a town in Wales with 40 bookshops.

Book Review: I keep getting caught by these kinds of books. To me Sixpence House was just like my read of The Year of Reading Dangerously by Andy Miller. I love nothing more than scavenging through used-book stores and charity shops, looking for that perfect book I didn't know I needed. So Sixpence House seemed right up my street. But no. This is more a memoir about him (quirky Yank), his family (fairly normal), and people in the town of Hay-on-Wye (oh, those quirky Brits!). One of my common gripes about movies and books is when they're quirky just to be quirky. It's never worked for me. Totally fair that he wrote the book he wanted to write, but I thought there'd be more in Sixpence House about books -- it's a town of books after all. So, this is an okay book, innocuous, neither good nor bad. And if I ever plan to travel to the magical town of Hay-on-Wye, I'll try to read Sixpence House again. I'll probably find it in a thrift store. [2.5 Stars]

Book Review: I keep getting caught by these kinds of books. To me Sixpence House was just like my read of The Year of Reading Dangerously by Andy Miller. I love nothing more than scavenging through used-book stores and charity shops, looking for that perfect book I didn't know I needed. So Sixpence House seemed right up my street. But no. This is more a memoir about him (quirky Yank), his family (fairly normal), and people in the town of Hay-on-Wye (oh, those quirky Brits!). One of my common gripes about movies and books is when they're quirky just to be quirky. It's never worked for me. Totally fair that he wrote the book he wanted to write, but I thought there'd be more in Sixpence House about books -- it's a town of books after all. So, this is an okay book, innocuous, neither good nor bad. And if I ever plan to travel to the magical town of Hay-on-Wye, I'll try to read Sixpence House again. I'll probably find it in a thrift store. [2.5 Stars]

Friday, July 22, 2016

Factotum by Charles Bukowski (1975)

Henry Chinaski leaves home and travels America, working hard at not working hard.

Book Review: One of my gripes about novels, movies, television, is that no one works, or at least it's rarely portrayed. Or if characters do work, jobs are something that can be fulfilled in a few minutes a day with some flirtation and a joke or two thrown in for good measure. Not the ravening beast that consumes half our lives and fill us with the fear of being fired and unable to pay the rent. Factotum is a novel about work.

In the Charles Bukowski story arc, Factotum follows Ham on Rye (and is then followed by Post Office); that's the best order to read them, if you can. Toward the end of Ham on Rye, Chinaski is desperate to leave home, to escape his parents, but won't try to keep a job so he can afford to leave home. In one of the early scenes of Factotum, Chinaski is working for $17 a week (!), after four days he demands a raise to $19, and quits when denied. The next week he takes a job for $12/week. That is the essence of Chinaski and Factotum: to be true to himself he will never commit to a job, work hard, or deny himself anything to keep working. Even if it means borderline disaster. Traveling across the country he finds job after job (explaining them in detail), and describes how the blue-collar working world operates. He knows how to play the game, he just chooses not to play. His attitude says he will never give in to the Man, no matter how much it hurts. The other half of that equation is, Charles Bukowski believes that working life is so stacked against the worker, that for any self-respecting person, there's no point in working. The first three-quarters of the book were quite good, but seemed to run out of steam toward the end. Factotum is vintage Bukowski, there's no plot, just a series of jobs and drinking, sex, race tracks, the occasional bit of philosophy. One of Bukowski's better books. And to save you the time of checking, a "factotum" is an employee or assistant who serves in a wide range of capacities. Appropriate title. [3.5 Stars]

Book Review: One of my gripes about novels, movies, television, is that no one works, or at least it's rarely portrayed. Or if characters do work, jobs are something that can be fulfilled in a few minutes a day with some flirtation and a joke or two thrown in for good measure. Not the ravening beast that consumes half our lives and fill us with the fear of being fired and unable to pay the rent. Factotum is a novel about work.

In the Charles Bukowski story arc, Factotum follows Ham on Rye (and is then followed by Post Office); that's the best order to read them, if you can. Toward the end of Ham on Rye, Chinaski is desperate to leave home, to escape his parents, but won't try to keep a job so he can afford to leave home. In one of the early scenes of Factotum, Chinaski is working for $17 a week (!), after four days he demands a raise to $19, and quits when denied. The next week he takes a job for $12/week. That is the essence of Chinaski and Factotum: to be true to himself he will never commit to a job, work hard, or deny himself anything to keep working. Even if it means borderline disaster. Traveling across the country he finds job after job (explaining them in detail), and describes how the blue-collar working world operates. He knows how to play the game, he just chooses not to play. His attitude says he will never give in to the Man, no matter how much it hurts. The other half of that equation is, Charles Bukowski believes that working life is so stacked against the worker, that for any self-respecting person, there's no point in working. The first three-quarters of the book were quite good, but seemed to run out of steam toward the end. Factotum is vintage Bukowski, there's no plot, just a series of jobs and drinking, sex, race tracks, the occasional bit of philosophy. One of Bukowski's better books. And to save you the time of checking, a "factotum" is an employee or assistant who serves in a wide range of capacities. Appropriate title. [3.5 Stars]

Wednesday, July 20, 2016

May Day by Gretchen Marquette (2016)

The first book by Minnesota poet, Gretchen Marquette, published in 2016.

Poetry Review: May Day by Gretchen Marquette is poetry as poetry should be; these are the kind of poems that could save poetry and make it something that real people actually read. I'm so sad that poetry has become a secret society, only read by other poets (& perhaps their patient friends), or by students required to attend readings by faculty poets. If not for slams, the word "poetry" might've been lost altogether.

The poems in May Day place cut-glass emotions into sharp relief against nature, talking in ways that speak to all of us, mind to mind, heart to heart, history to history. With an image of a wounded doe in mind, she writes: "Don't think on it too long./I know I'd die of thirst," and we're deep in Marquette's history, a history that mixes with ours, parallel or shared. These poems dance through time, of childhood, parents and brothers, of lovers lost and summers past, a memory sleeping in the next room. A poem about a turtle on a road cries out, "Why aren't I your wife?" There are deer, forest, fishermen, cows, hawks, dogs, and they morph at any moment into this instant's thought: Iraq, hurt, the pain of love, loss. Poems with blood, with subtle undertones of Plath (almost unavoidable, I think), and moments touched by Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca (1898-1936), that Marquette has made all her own: "... my lost dolls,/your small guitar, and my broken horses." Her influences have been absorbed deep into the bones of these mature, well made poems. There are so many lines that just kill me: "You've got all the words/though I go on, fumbling./Let me learn another language" and "Spring has arrived./Let me not despair."

Without counting, more than half the poems in May Day are so powerful, so resonant, pointing the way to a book that could rip trees out of the ground. So what didn't I like? Sometimes it's a little too trendy, post-modernist for me: Gretchen Marquette is strongest when simply communicating through her exact and pointed images, stripped naked, without throwing in the requisite academic tropes. And there's also the occasional scientific factoids, dropped in like raisins, that I've also noticed in works by other poets, so it may now be a trend that's crept into the business. I may be wrong, my prejudice showing, but the best poems here come straight from Marquette's bones, without the stylish overlay that make them beloved of academics and journals (this is all from Lorca's "Play and Theory of the Duende," which I'm sure Marquette has read.) When she lets the duende break through, I'd put her words up against anyone writing today. The poems in May Day have a depth, a humanity, that is all too rare in our world. A second book by Gretchen Marquette is a necessity. [4 Stars]

Poetry Review: May Day by Gretchen Marquette is poetry as poetry should be; these are the kind of poems that could save poetry and make it something that real people actually read. I'm so sad that poetry has become a secret society, only read by other poets (& perhaps their patient friends), or by students required to attend readings by faculty poets. If not for slams, the word "poetry" might've been lost altogether.

The poems in May Day place cut-glass emotions into sharp relief against nature, talking in ways that speak to all of us, mind to mind, heart to heart, history to history. With an image of a wounded doe in mind, she writes: "Don't think on it too long./I know I'd die of thirst," and we're deep in Marquette's history, a history that mixes with ours, parallel or shared. These poems dance through time, of childhood, parents and brothers, of lovers lost and summers past, a memory sleeping in the next room. A poem about a turtle on a road cries out, "Why aren't I your wife?" There are deer, forest, fishermen, cows, hawks, dogs, and they morph at any moment into this instant's thought: Iraq, hurt, the pain of love, loss. Poems with blood, with subtle undertones of Plath (almost unavoidable, I think), and moments touched by Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca (1898-1936), that Marquette has made all her own: "... my lost dolls,/your small guitar, and my broken horses." Her influences have been absorbed deep into the bones of these mature, well made poems. There are so many lines that just kill me: "You've got all the words/though I go on, fumbling./Let me learn another language" and "Spring has arrived./Let me not despair."

Without counting, more than half the poems in May Day are so powerful, so resonant, pointing the way to a book that could rip trees out of the ground. So what didn't I like? Sometimes it's a little too trendy, post-modernist for me: Gretchen Marquette is strongest when simply communicating through her exact and pointed images, stripped naked, without throwing in the requisite academic tropes. And there's also the occasional scientific factoids, dropped in like raisins, that I've also noticed in works by other poets, so it may now be a trend that's crept into the business. I may be wrong, my prejudice showing, but the best poems here come straight from Marquette's bones, without the stylish overlay that make them beloved of academics and journals (this is all from Lorca's "Play and Theory of the Duende," which I'm sure Marquette has read.) When she lets the duende break through, I'd put her words up against anyone writing today. The poems in May Day have a depth, a humanity, that is all too rare in our world. A second book by Gretchen Marquette is a necessity. [4 Stars]

Monday, July 18, 2016

Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage by Haruki Murakami (2013)

One of five inseparable high-school friends is inexplicably expelled from the group, which changes his life for the next 16 years, when he finally determines to learn the reason for his exclusion.

Book Review: If E.M. Forster said "Only connect," Haruki Murakami says "How?" In Colorless Tsukuru and His Years of Pilgrimage, Murakami explores the difficult mix of commitment and connection, when broken commitments lead to failed relationships. The eponymous character is insecure from the beginning, seeing himself as "colorless," with "a constant nagging fear" of losing his friends, which when he does his "life was changed forever." The loss affects everything, even his appearance changes. And that is the story of Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage (Murakami's 13th novel). This, tho written in the third person, is more like Norwegian Wood and Sputnik Sweetheart (than The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle or Kafka on the Shore), but less love-sick, and the romance is told more from a more restrained adult perspective, and is an attempt to change his life. Something like Norwegian Wood grown up. As always, Murakami manages to infuse every page with our hero's struggles, his spiraling emotions, depths and highs, black and white with infinite shades of gray, his thoughts moving between high school and the present day. Tazaki's international quest to learn what happened in his past, and so save his present, is what so forcefully drives this book. Quietly powerful, this is another valuable addition to the Murakami canon (ably translated by Philip Gabriel), with many of his typical tropes and quirks, but also his insights into and descriptions of emotions. Rather than tell more about the novel and risk spoilers, I'll end with this description of the moment when Tazaki is first about to confront his past:

Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage extends Murakami's reach, and shows us more of what he can do, what he wants to do. [4.5 Stars]

Book Review: If E.M. Forster said "Only connect," Haruki Murakami says "How?" In Colorless Tsukuru and His Years of Pilgrimage, Murakami explores the difficult mix of commitment and connection, when broken commitments lead to failed relationships. The eponymous character is insecure from the beginning, seeing himself as "colorless," with "a constant nagging fear" of losing his friends, which when he does his "life was changed forever." The loss affects everything, even his appearance changes. And that is the story of Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage (Murakami's 13th novel). This, tho written in the third person, is more like Norwegian Wood and Sputnik Sweetheart (than The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle or Kafka on the Shore), but less love-sick, and the romance is told more from a more restrained adult perspective, and is an attempt to change his life. Something like Norwegian Wood grown up. As always, Murakami manages to infuse every page with our hero's struggles, his spiraling emotions, depths and highs, black and white with infinite shades of gray, his thoughts moving between high school and the present day. Tazaki's international quest to learn what happened in his past, and so save his present, is what so forcefully drives this book. Quietly powerful, this is another valuable addition to the Murakami canon (ably translated by Philip Gabriel), with many of his typical tropes and quirks, but also his insights into and descriptions of emotions. Rather than tell more about the novel and risk spoilers, I'll end with this description of the moment when Tazaki is first about to confront his past:

"The sky was covered with a thin layer of clouds, not a patch of blue visible anywhere, though it did not look like rain. There was no wind, either. The branches of a nearby willow tree were laden with lush foliage and drooping heavily, almost to the ground, though they were still, as if lost in deep thought. Occasionally a small bird landed unsteadily on a branch, but soon gave up and fluttered away. Like a distraught mind, the branch quivered slightly, then returned to stillness."

Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage extends Murakami's reach, and shows us more of what he can do, what he wants to do. [4.5 Stars]

Saturday, July 16, 2016

Book Thoughts: The Arrangements by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (2016)

Virginia Woolf and Donald Trump, the perfect couple? Say what now? A belated mention of this recent brief work, The Arrangements, by the author of Americanah, in the 3 July issue of the New York Times Book Review (it's an e-book, also). In her new short story, Adichie has rewritten Virginia Woolf, with Melania Trump (Mrs. Donald Trump) in the role of Mrs. Dalloway in Mrs. Dalloway. The Book Review states that for the first time ever, it had commissioned an original short story, addressing "anything about this election season." Adichie chose Mrs. Trump and, in reality, Mr. Trump. Adichie's The Arrangements consists of the thoughts of, and conversations with, Melania Trump, combining Virginia Woolf with the headlines and news stories of today. She thus introduces us to the imagined inner life of the mostly silent wife of the much praised and much attacked presumptive Republican presidential nominee. The thoughts described seem eerily probable, more credit to Adichie, as non-fiction credibility rings through the fictional feel of the writing, the Woolfian echoes clear and bright. I won't make any editorial comments here about The Arrangements, merely wanting to make more people aware of this new short story. Here is a new work by, and the point of view of, the Nigerian novelist who is also a graduate of Johns Hopkins and Yale universities. Which begs the question, what would Virginia Woolf have made of Trumpism? Seek it out, enjoy, ponder.

Friday, July 15, 2016

South of the Border, West of the Sun by Haruki Murakami (1992)

A middle-aged man re-evaluates relationships with the three women in his life when an idealized girl from his childhood reappears, now a grown, mysterious woman.

Book Review: A book about growing up, making choices, being the right person, facing consequences. South of the Border, West of the Sun is Haruki Murakami's study of a man's relationship with and treatment of the three women he has loved. As with so many of Murakami's books, the ending left me satisfied, but with a wee bit of mystery. Although obsessed with the enigmatic girl from his childhood (known only by her surname), as the protagonist (Hajime) re-engages with her, he gradually realizes the hurt and damage he's inflicted on those he's loved. He learns about consequences and faces death, even while sometimes still trying to justify his actions, and even if she still wants to make the wrong choices. South of the Border, West of the Sun, his seventh novel, falls into Murakami's minimally magical, first-person narrator books such as Norwegian Wood and Sputnik Sweetheart, rather than the fantastical Wind-Up Bird Chronicle or Kafka on the Shore. Here, Hajime learns that women are human beings and don't simply exist to meet his needs. How the lesson is taught is the story of this book, which I didn't fully realize (at first, I'd focused too much on the plot and the mystery woman) until a second reading. It would be easy to dismiss South of the Border, West of Sun as obvious or simplistic, if the conflict in the book wasn't one that so many women and men (even in Japan, apparently) suffer through, until men become adults (if they do), and infidelity is no longer an exciting thrill, but a hurtful betrayal of the loved one (overcoming the "conquest" culture). As with so much of Haruki Murakami's writing there is a strong undertone of modern fairy tale, perhaps to explain the purpose of the mystery woman's reappearance in his life. In the end, Hajime realizes that "a person can, just by living, damage another human being beyond repair." Ably translated by Philip Gabriel, this is excellent, honest, challenging, classic Murakami. [4 Stars]

Book Review: A book about growing up, making choices, being the right person, facing consequences. South of the Border, West of the Sun is Haruki Murakami's study of a man's relationship with and treatment of the three women he has loved. As with so many of Murakami's books, the ending left me satisfied, but with a wee bit of mystery. Although obsessed with the enigmatic girl from his childhood (known only by her surname), as the protagonist (Hajime) re-engages with her, he gradually realizes the hurt and damage he's inflicted on those he's loved. He learns about consequences and faces death, even while sometimes still trying to justify his actions, and even if she still wants to make the wrong choices. South of the Border, West of the Sun, his seventh novel, falls into Murakami's minimally magical, first-person narrator books such as Norwegian Wood and Sputnik Sweetheart, rather than the fantastical Wind-Up Bird Chronicle or Kafka on the Shore. Here, Hajime learns that women are human beings and don't simply exist to meet his needs. How the lesson is taught is the story of this book, which I didn't fully realize (at first, I'd focused too much on the plot and the mystery woman) until a second reading. It would be easy to dismiss South of the Border, West of Sun as obvious or simplistic, if the conflict in the book wasn't one that so many women and men (even in Japan, apparently) suffer through, until men become adults (if they do), and infidelity is no longer an exciting thrill, but a hurtful betrayal of the loved one (overcoming the "conquest" culture). As with so much of Haruki Murakami's writing there is a strong undertone of modern fairy tale, perhaps to explain the purpose of the mystery woman's reappearance in his life. In the end, Hajime realizes that "a person can, just by living, damage another human being beyond repair." Ably translated by Philip Gabriel, this is excellent, honest, challenging, classic Murakami. [4 Stars]

Wednesday, July 13, 2016

Sputnik Sweetheart by Haruki Murakami (1999)

A young man is in love with his only friend, who's in love with another woman who doesn't love her, and then something strange happens.

Book Review: Sputnik Sweetheart only touches on the bizarre, and is closer in style to Norwegian Wood than Haruki Murakami's more magical or fantastical books such as The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle or Kafka on the Shore. Our unnamed first-person narrator ("K") is in love with his close friend from school, Sumire, but she is in love with her employer, Miu, an older married woman. The blurb on the back of Sputnik Sweetheart gives away the main event, which occurs about halfway through the book (so I won't). Not a lot happens in Sputnik Sweetheart; much of it is about unfulfilled passions. K wants to fulfill his relationship with Sumire, but is resigned to remaining her friend. Sumire drops out of school to fulfill her passion to be a writer, but is unsuccessful and finally gives it up when she falls in love with Miu, but her love is unrequited and that passion too is unfulfilled. Miu has lost her passion and lives only an, outwardly perfect, half-life. So rather than a love triangle we have a "love line-segment." The book is filled with doubles and triples of loss and longing. Murakami writes of the dog Laika, fated to die alone in Sputnik 2, or a cat that went up a tree and disappeared. Sumire worries that her love will cause her to lose everything, as a chunk of ice left in the sun, that time will leave her behind, that she is being reinvented, but to what end? Gradually she feels less and less herself. Sumire has a long dream sequence about her lost mother. Miu has lost herself and is only half a person. Murakami also uses this book to deploy his collection of similes: "I was as exhausted as an old railroad tie"; "books that didn't fit into the bookshelf lay piled on the floor like a bunch of intellectual refugees."

This quiet book is classic Haruki Murakami, (well translated by Philip Gabriel), but mostly involving passion over plot, and leads to an extended ending: Sputnik Sweetheart ends maybe two or three times, but then keeps going until the final uncertain conclusion. What really happened is up to the reader; how the reader feels about Sputnik Sweetheart will largely depend on how the reader feels about the ending(s). Tho quieter, less dramatic, less magical that his other books, Sputnik Sweetheart, (Murakami's ninth novel) is still enjoyable, an extended reverie, an emotional experience well worth reading. [4 Stars]

Book Review: Sputnik Sweetheart only touches on the bizarre, and is closer in style to Norwegian Wood than Haruki Murakami's more magical or fantastical books such as The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle or Kafka on the Shore. Our unnamed first-person narrator ("K") is in love with his close friend from school, Sumire, but she is in love with her employer, Miu, an older married woman. The blurb on the back of Sputnik Sweetheart gives away the main event, which occurs about halfway through the book (so I won't). Not a lot happens in Sputnik Sweetheart; much of it is about unfulfilled passions. K wants to fulfill his relationship with Sumire, but is resigned to remaining her friend. Sumire drops out of school to fulfill her passion to be a writer, but is unsuccessful and finally gives it up when she falls in love with Miu, but her love is unrequited and that passion too is unfulfilled. Miu has lost her passion and lives only an, outwardly perfect, half-life. So rather than a love triangle we have a "love line-segment." The book is filled with doubles and triples of loss and longing. Murakami writes of the dog Laika, fated to die alone in Sputnik 2, or a cat that went up a tree and disappeared. Sumire worries that her love will cause her to lose everything, as a chunk of ice left in the sun, that time will leave her behind, that she is being reinvented, but to what end? Gradually she feels less and less herself. Sumire has a long dream sequence about her lost mother. Miu has lost herself and is only half a person. Murakami also uses this book to deploy his collection of similes: "I was as exhausted as an old railroad tie"; "books that didn't fit into the bookshelf lay piled on the floor like a bunch of intellectual refugees."

This quiet book is classic Haruki Murakami, (well translated by Philip Gabriel), but mostly involving passion over plot, and leads to an extended ending: Sputnik Sweetheart ends maybe two or three times, but then keeps going until the final uncertain conclusion. What really happened is up to the reader; how the reader feels about Sputnik Sweetheart will largely depend on how the reader feels about the ending(s). Tho quieter, less dramatic, less magical that his other books, Sputnik Sweetheart, (Murakami's ninth novel) is still enjoyable, an extended reverie, an emotional experience well worth reading. [4 Stars]

Monday, July 11, 2016

The Strange Library by Haruki Murakami (2005)

During a visit to the library, a boy is imprisoned in a labyrinth beneath the building.

This was very much a "what the heck?" moment for me. The Strange Library is a short story (can be read at a sitting) dressed up in a fancy package with odd flaps, interesting pictures, and creative art. A scary book (brains may be eaten), which I assume was written for kids. But if I was a kid reading this, I'd never go to another library. It's still Murakami: a frightening old man (ageism rears its ugly head), a beautiful mute girl, bizarre events, a maze, alternate dimensions, and the Sheep Man from A Wild Sheep Chase even makes an appearance (tho his speech pattern has changed since that book -- why?). I can forgive Haruki Murakami anything, and perhaps kids will understand The Strange Library better than I did. I kept waiting for the more, that never arrived. The ending was quick and easy (deus ex machina), but with unexplained elements, and a quite sad epilogue, in smaller print, that readers might easily miss. It's all straight forward and linear, but it seems I missed something that Murakami was trying to tell. The translation by Ted Goossen was adequate, but there were still a couple "is that the right word?" moments. In the end, The Strange Library, (his 14th novel) is a simple, abbreviated adventure story, that won't take up too much of your time, and you'll get a wee taste of Haruki Murakami at the same time. [2.5 Stars]

This was very much a "what the heck?" moment for me. The Strange Library is a short story (can be read at a sitting) dressed up in a fancy package with odd flaps, interesting pictures, and creative art. A scary book (brains may be eaten), which I assume was written for kids. But if I was a kid reading this, I'd never go to another library. It's still Murakami: a frightening old man (ageism rears its ugly head), a beautiful mute girl, bizarre events, a maze, alternate dimensions, and the Sheep Man from A Wild Sheep Chase even makes an appearance (tho his speech pattern has changed since that book -- why?). I can forgive Haruki Murakami anything, and perhaps kids will understand The Strange Library better than I did. I kept waiting for the more, that never arrived. The ending was quick and easy (deus ex machina), but with unexplained elements, and a quite sad epilogue, in smaller print, that readers might easily miss. It's all straight forward and linear, but it seems I missed something that Murakami was trying to tell. The translation by Ted Goossen was adequate, but there were still a couple "is that the right word?" moments. In the end, The Strange Library, (his 14th novel) is a simple, abbreviated adventure story, that won't take up too much of your time, and you'll get a wee taste of Haruki Murakami at the same time. [2.5 Stars]

Friday, July 8, 2016

Norwegian Wood by Haruki Murakami (1987)

After a death, two friends become closer, and try to move on with life in a web of friendship, loss, love, and struggle.

Book Review: While reading Norwegian Wood, I kept thinking that it was the Romeo and Juliet of our time, and although that isn't quite right, it isn't all wrong either. Set in the late Sixties, Haruki Murakami tells his story through the intertwined lives of seven people, all of whom become involved with one or more of the other characters, and provide parallels and counterpoint to the others. The two pillars of this novel are the emotion and insight Murakami creates though an accumulation of intense and minute detail, and the way he weaves the central actors together, their actions highlighting others' actions, comparing and contrasting them, one relationship putting another into sharp relief. The actions of one person affects others who never knew she or he existed, like the wings of the butterfly. As Murakami is quoted in the Translator's Note, Norwegian Wood, his fifth novel) is a change for him, just a "kind of straight, simple story." And without the fantastic, without magical realism, without flights of fancy, he does his simple story brilliantly. This is a sensual and physical story, adult even, but that is the least of what this is about. Yes Murakami captures the eroticism of youth and the sixties, but Norwegian Wood is about the opposite of that, and I'm surprised by those who get hung up on the sex and fail to see the much more important story Murakami is telling.

This book is being written by a character who finds he has "to write things down to feel I fully comprehend them." A loner, he falls in love with a girl who asks that he "promise never to forget" her. His favorite book is The Great Gatsby, and as in that book there's the question whether Gatsby and Daisy, or the other people in life, are the "twisted" ones, or the ones lost in a "cold, dark place." I think Norwegian Wood is a brilliant and open, but blindingly subtle book, the real emotions and lessons hidden beneath the surface, and told in immaculate detail. Wonderfully translated by Jay Rubin, this is a book to read and appreciate, and read again. [5 Stars]

Book Review: While reading Norwegian Wood, I kept thinking that it was the Romeo and Juliet of our time, and although that isn't quite right, it isn't all wrong either. Set in the late Sixties, Haruki Murakami tells his story through the intertwined lives of seven people, all of whom become involved with one or more of the other characters, and provide parallels and counterpoint to the others. The two pillars of this novel are the emotion and insight Murakami creates though an accumulation of intense and minute detail, and the way he weaves the central actors together, their actions highlighting others' actions, comparing and contrasting them, one relationship putting another into sharp relief. The actions of one person affects others who never knew she or he existed, like the wings of the butterfly. As Murakami is quoted in the Translator's Note, Norwegian Wood, his fifth novel) is a change for him, just a "kind of straight, simple story." And without the fantastic, without magical realism, without flights of fancy, he does his simple story brilliantly. This is a sensual and physical story, adult even, but that is the least of what this is about. Yes Murakami captures the eroticism of youth and the sixties, but Norwegian Wood is about the opposite of that, and I'm surprised by those who get hung up on the sex and fail to see the much more important story Murakami is telling.

This book is being written by a character who finds he has "to write things down to feel I fully comprehend them." A loner, he falls in love with a girl who asks that he "promise never to forget" her. His favorite book is The Great Gatsby, and as in that book there's the question whether Gatsby and Daisy, or the other people in life, are the "twisted" ones, or the ones lost in a "cold, dark place." I think Norwegian Wood is a brilliant and open, but blindingly subtle book, the real emotions and lessons hidden beneath the surface, and told in immaculate detail. Wonderfully translated by Jay Rubin, this is a book to read and appreciate, and read again. [5 Stars]

Wednesday, July 6, 2016

The Unsubscriber by Bill Knott (2004)

The eleventh book by American poet Bill Knott (1940-2014).

Poetry Review: The Unsubscriber is Bill Knott's mature work, having grown and learned much since his first, 1968's The Naomi Poems. Sure there are hints and ghosts of his old work here, but this book was written by a grown man, older, wiser, better read, and more thoughtful than that youthful self. Not quite as angry, not as direct, less obscenity and thrilling to dirty words, a harder book than those from his early days, no longer a voice from the hippie '60s. No one was more aggressively self-deprecating than Bill Knott, both railing against a world that refused to reward or recognize him or poets in general, and proclaiming his utter failure and the abysmal flaws of his work. But this book came from a prestigious publishing house (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), and I think Knott recognized the opportunity he had and threw every ounce of himself into this volume. There are long poems, a section of his beloved short poems, sonnets, haiku, poems of 9 or 11 lines, everything he could do. The Unsubscriber is difficult, but full of rhyme, puns, surrealism, wordplay, half-rhyme, portmanteau words. The Tower of Babel, Noah, Ripley (from Alien), Wallace Stevens (obliquely), Plath & Hughes, Damocles, Isadora Duncan, Sappho and Pope Gregory VII, Kerouac, Borges, Trakl, Basho, Adrienne Rich ("All future poets can be coined ... from the DNA of ..."), the Rolling Stones, and others form the cast of these poems. The poems are serious, deep, dense (Knott acknowledges the existence of "too many recondite allusions"). He adds footnotes to shine a spotlight on his methods: no secrets here! In a way, these are poems for poets, who could write three poems from each of these. The influence of James Joyce, maybe Dylan Thomas too, probably others I'm not even qualified to discern, is felt.

Bill Knott is the unsubscriber, the compleat iconoclast who never followed any hierarchy, who precisely walked his own road. And dense as some of the poems may be, there are wonderful lines that speak clearly:

A poem is a room that contains

the house it's in

As usual a metaphor

Meant to make up for

My lack of coherence

Always jumping from one pan

of the scale to the other, always

trying to measure

your absence.

... to remove

all consonants from our star-maps.

The infinite consists of vowels alone.

Sometimes the poems are more difficult, but always rewarding, with an underlying anger that builds slowly as The Unsubscriber goes on. Two issues enrage the author here: the current and coming environmental disaster that Knott terms ecocide ("Join Jack and his pals/in the endless adventure/of spilling fossil fuels/into the atmosphere"), and the crime of maleness, the sins committed by men ("Males must become an extinct species."):

So I blame him and him and him and him,

All of them from Adam onwards are men,

Meaning me, meaning the worst thing I know.

For Bill Knott, self-hatred is never too far from the surface. All I've mentioned above just scratches the surface. I found The Unsubscriber difficult, defiant, provocative, slowly enriching. And surprisingly I found it at my local library (the benefit of being on FSG). If you're a poet, in self or soul, this could be the challenge you need. [4 Stars].

Poetry Review: The Unsubscriber is Bill Knott's mature work, having grown and learned much since his first, 1968's The Naomi Poems. Sure there are hints and ghosts of his old work here, but this book was written by a grown man, older, wiser, better read, and more thoughtful than that youthful self. Not quite as angry, not as direct, less obscenity and thrilling to dirty words, a harder book than those from his early days, no longer a voice from the hippie '60s. No one was more aggressively self-deprecating than Bill Knott, both railing against a world that refused to reward or recognize him or poets in general, and proclaiming his utter failure and the abysmal flaws of his work. But this book came from a prestigious publishing house (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), and I think Knott recognized the opportunity he had and threw every ounce of himself into this volume. There are long poems, a section of his beloved short poems, sonnets, haiku, poems of 9 or 11 lines, everything he could do. The Unsubscriber is difficult, but full of rhyme, puns, surrealism, wordplay, half-rhyme, portmanteau words. The Tower of Babel, Noah, Ripley (from Alien), Wallace Stevens (obliquely), Plath & Hughes, Damocles, Isadora Duncan, Sappho and Pope Gregory VII, Kerouac, Borges, Trakl, Basho, Adrienne Rich ("All future poets can be coined ... from the DNA of ..."), the Rolling Stones, and others form the cast of these poems. The poems are serious, deep, dense (Knott acknowledges the existence of "too many recondite allusions"). He adds footnotes to shine a spotlight on his methods: no secrets here! In a way, these are poems for poets, who could write three poems from each of these. The influence of James Joyce, maybe Dylan Thomas too, probably others I'm not even qualified to discern, is felt.

Bill Knott is the unsubscriber, the compleat iconoclast who never followed any hierarchy, who precisely walked his own road. And dense as some of the poems may be, there are wonderful lines that speak clearly:

A poem is a room that contains

the house it's in

As usual a metaphor

Meant to make up for

My lack of coherence

Always jumping from one pan

of the scale to the other, always

trying to measure

your absence.

... to remove

all consonants from our star-maps.

The infinite consists of vowels alone.

Sometimes the poems are more difficult, but always rewarding, with an underlying anger that builds slowly as The Unsubscriber goes on. Two issues enrage the author here: the current and coming environmental disaster that Knott terms ecocide ("Join Jack and his pals/in the endless adventure/of spilling fossil fuels/into the atmosphere"), and the crime of maleness, the sins committed by men ("Males must become an extinct species."):

So I blame him and him and him and him,

All of them from Adam onwards are men,

Meaning me, meaning the worst thing I know.

For Bill Knott, self-hatred is never too far from the surface. All I've mentioned above just scratches the surface. I found The Unsubscriber difficult, defiant, provocative, slowly enriching. And surprisingly I found it at my local library (the benefit of being on FSG). If you're a poet, in self or soul, this could be the challenge you need. [4 Stars].

Monday, July 4, 2016

After Dark by Haruki Murakami (2004)

We (literally) watch four characters from 11:56 one night until 6:52 the next morning, as their lives engage and disengage through various dimensions.

Book Review: After Dark isn't mentioned as often as Haruki Murakami's other books, but should be. This book was short, odd, voyeuristic, magical, and never ceased to entertain and absorb. Written in the first person plural, as if a film script or following the ghost of Christmas present, we watch a young woman embarking into life, her beautiful sister who sleeps on in a techno-fairy tale, a young musician who's facing his own life events, and the evil found in the dark twisted mind of a married salaryman. Certain sections of After Dark, such as the discussions between the young woman and the musician, seem all too real, while other sections, some very brief, are Haruki Murakami making magical realism or a modern fable or fairy tale. The structure of the book is a series of moments throughout a night with one or more of our four avatars, where an event occurs, and very little happens, and it all ties together in some dimension that intellectually we don't quite comprehend, but we understand emotionally. In the end that's what I enjoyed most about After Dark: I didn't have to fully understand it to get it -- Haruki Murakami is writing more for your heart and soul than your mind. And the translation by Jay Rubin is smooth and practically transparent; I like when I don't have to think about the translation. His 11th novel, this isn't one of Murakami's larger or more ambitious efforts, full of fantastical creatures and incredible events, but it is modern. Here he had a tale to tell, and he tells it wonderfully. [4 Stars]

Book Review: After Dark isn't mentioned as often as Haruki Murakami's other books, but should be. This book was short, odd, voyeuristic, magical, and never ceased to entertain and absorb. Written in the first person plural, as if a film script or following the ghost of Christmas present, we watch a young woman embarking into life, her beautiful sister who sleeps on in a techno-fairy tale, a young musician who's facing his own life events, and the evil found in the dark twisted mind of a married salaryman. Certain sections of After Dark, such as the discussions between the young woman and the musician, seem all too real, while other sections, some very brief, are Haruki Murakami making magical realism or a modern fable or fairy tale. The structure of the book is a series of moments throughout a night with one or more of our four avatars, where an event occurs, and very little happens, and it all ties together in some dimension that intellectually we don't quite comprehend, but we understand emotionally. In the end that's what I enjoyed most about After Dark: I didn't have to fully understand it to get it -- Haruki Murakami is writing more for your heart and soul than your mind. And the translation by Jay Rubin is smooth and practically transparent; I like when I don't have to think about the translation. His 11th novel, this isn't one of Murakami's larger or more ambitious efforts, full of fantastical creatures and incredible events, but it is modern. Here he had a tale to tell, and he tells it wonderfully. [4 Stars]

Friday, July 1, 2016

The Sirens Sang of Murder by Sarah Caudwell (1989)

One of our intrepid barristers has traveled from the Channel Islands to Monte Carlo, with murder in the offing, and Professor Tamar must follow to the rescue.

Book Review: This time it's the energetic if callow Cantrip sending missives back to 63 New Square in this third installment of Sarah Caudwell's Professor Hilary Tamar series, The Sirens Sang of Murder. Here we have Jersey, Guernsey (of Potato Peel Society fame), and Sark, tax-law, missing heirs, London, the new-fangled telex, Monte Carlo, locked wine cellars, helicopters, and, of course, murder. Each book in the Professor Tamar series seems just a wee bit better than one before, and the only true tragedy is that there is only one more book (The Sibyl in Her Grave) left in the series. Actually, one is not required to read the books of the Hilary Tamar series in order, each stands alone, but I've found it more enjoyable to do so, as I think Caudwell, of course, expected. And let me save everyone some time: it's inconceivable that anyone who enjoyed one of the books would find any of the others anything less than equally entertaining. All, including The Sirens Sang of Murder, are of equally high quality. All are very English, full of lawyers, full of humor (more dry than wet), arch, wry, consistently clever, with a dash of sex. And all are "cozy" mysteries, or at least a humorous take on the cozy mystery. We learn to know and love Sarah Caudwell's cast: the curvy and amorous Julia, the perfectly professional Selena, Ragwort of the chiseled profile, the youthfully enthusiastic Cantrip, and of course the immaculate and always indeterminate Professor Hilary Tamar, who solves crimes due to her scholarly qualities. If you like your mystery leavened with a little (or a lot of) dry humor, you may well enjoy the books, Thus Was Adonis Murdered, The Shortest Way to Hades, and now The Sirens Sang of Murder, as much as I do. [4.5 Stars]

Book Review: This time it's the energetic if callow Cantrip sending missives back to 63 New Square in this third installment of Sarah Caudwell's Professor Hilary Tamar series, The Sirens Sang of Murder. Here we have Jersey, Guernsey (of Potato Peel Society fame), and Sark, tax-law, missing heirs, London, the new-fangled telex, Monte Carlo, locked wine cellars, helicopters, and, of course, murder. Each book in the Professor Tamar series seems just a wee bit better than one before, and the only true tragedy is that there is only one more book (The Sibyl in Her Grave) left in the series. Actually, one is not required to read the books of the Hilary Tamar series in order, each stands alone, but I've found it more enjoyable to do so, as I think Caudwell, of course, expected. And let me save everyone some time: it's inconceivable that anyone who enjoyed one of the books would find any of the others anything less than equally entertaining. All, including The Sirens Sang of Murder, are of equally high quality. All are very English, full of lawyers, full of humor (more dry than wet), arch, wry, consistently clever, with a dash of sex. And all are "cozy" mysteries, or at least a humorous take on the cozy mystery. We learn to know and love Sarah Caudwell's cast: the curvy and amorous Julia, the perfectly professional Selena, Ragwort of the chiseled profile, the youthfully enthusiastic Cantrip, and of course the immaculate and always indeterminate Professor Hilary Tamar, who solves crimes due to her scholarly qualities. If you like your mystery leavened with a little (or a lot of) dry humor, you may well enjoy the books, Thus Was Adonis Murdered, The Shortest Way to Hades, and now The Sirens Sang of Murder, as much as I do. [4.5 Stars]

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)