A capable compendium for the beginning poetry consumer.

Book Review: How to Read Poetry Like a Professor is solid, useful, practical. You won't go wrong with this one. That it's not the ideal Platonic archetype I've been seeking isn't Foster's fault. I've been looking for a basic introduction to reading poetry, and this ticks off most, though not all, of the boxes. My gentle fault-finding begins with the order in which the author presents his topics. Foster begins with the sounds of words (such as "those hard g and k sounds"). Although important, for me this is one of the more esoteric elements, I find it comes naturally to many readers and writers, and way too much is made of it when evaluating poetry. Next he turns to meter (y'know, iambic pentameter, etc.), also esoteric, somewhat of a lost art (though making a comeback), and not truly scintillating. While both subjects need to be addressed, I'd put them off till the end to not discourage faint-hearted readers. Maybe begin with the oral tradition, discuss slam poetry, and then after intriguing the reader move on to the more academic topics. I know my criticism is completely subjective, but I say this because I found the first half of How to Read Poetry Like a Professor slow-going and was ready to quit. The second half picked up and saved my read. In fairness, he does work hard at making the book as interesting and fun as possible. Another small critique is a certain lack of diversity in the examples provided, which I'll credit to trying to keep down the number of copyrights. When I read Foster's previous book, How to Read Literature Like a Professor, I found it good at the time, but since then it has seemed even better in retrospect -- always a good sign when a book gets better over time. Perhaps How to Read Poetry Like a Professor will have the same effect. [3★]

Monday, April 30, 2018

Friday, April 27, 2018

The Hatred of Poetry by Ben Lerner (2016)

A lengthy essay on the thesis that everyone is justified in hating poetry.

Book Review: The Hatred of Poetry just made me feel contrary. I don't hate poetry and while some poets may be misdirected, and some poems inscrutable, naturally the only proper and logical course is to hate the poets -- not poetry. Certainly poetry is often taught poorly. A few years ago I had the good fortune to teach an evening continuing-education class in poetry writing and it was lovely. Housewives, farmers, grandmas, working folk, and the odd regular student or two, all ages and types and all with the desire to love and write poetry. The quality of the poems may've been all over the place, ranging from a crow on a fence at sunset (worthy of Bashō), to Mickey Mouse, to how a country row of mailboxes resembled gravestones, to teenage heartbreak. My students were wonderfully generous and helpful with each other, always self-deprecating, eager to learn, to improve, to express their visions. They were also tolerant of and patient with my not-well-informed but well-meaning suggestions. That class was a highlight of my life and it all blossomed from a shared love, not hatred, of poetry. Ben Lerner in The Hatred of Poetry seems to believe that poetry deserves to be hated, but to me this is mean-spirited. Small minded. More clever than meaningful. But an excellent way for an academic to get a grant. Ben Lerner's thesis rests on two fallible points: first, that poets, unlike other artists, fail to achieve the transformation of their poetic vision into substance. But all artists suffer this frustration. How many painters have taken knives to canvas? How many novels have been burned in manuscript? How many songs died aborning, never being heard? (In fact, Lerner's root example is song, not poetry.) As George Orwell said, "Every book is a failure." Or William Faulkner: "We will all agree that we failed. That what we made never ... will match the shape, the dream of perfection which ... will continue to drive us, even after each failure, until anguish frees us and the hand falls still at last." Or da Vinci: "Art is never finished, only abandoned." I can't say that any poet is a greater or more frustrated artist than Toni Morrison, Pablo Picasso, Beethoven, or Yo-Yo Ma. Lerner's second point is that poets must be simultaneously relevant and universal. Yet so much amazing poetry is neither and never attempted to be either. Much reasonably modern poetry (yes, you, Language Poetry) is completely opaque. It's neither relevant nor universal, but is certainly poetry (no, I'm not a fan, 'nuff said). There are other odd moments: Lerner eviscerates a fellow white male poet for being more of a white male than he. As a poet he's ready to leap into the cliche simile of "like a sensation in a phantom limb." And while he appreciates Dickinson he finds Whitman wanting because "Whitman's dreamed union never arrived." Yet he seems to miss that Dickinson's tiny, hermetic, insular poems spoke to the broadest universal themes and passions, while Whitman's Old Testament prophet voice spoke to a very individual and personal, almost confessional view of himself: the great "I" as well as "We." He does note Charles Olson's accurate observation that lines of poems are more poetically striking when quoted in prose than in the actual source poem itself; I've always found that true and puzzling. My thought here is not to discourage anyone from reading The Hatred of Poetry. It's worth reading. But pack a rucksack full of salt, keep your skepticism at hand, and always, always, always question authority. The moments I've had reading Lorca, Dickinson, Neruda, and too many others are moments I treasure. Just read "Death of a Son" by Jon Silkin, and who could hate poetry? [3★]

Book Review: The Hatred of Poetry just made me feel contrary. I don't hate poetry and while some poets may be misdirected, and some poems inscrutable, naturally the only proper and logical course is to hate the poets -- not poetry. Certainly poetry is often taught poorly. A few years ago I had the good fortune to teach an evening continuing-education class in poetry writing and it was lovely. Housewives, farmers, grandmas, working folk, and the odd regular student or two, all ages and types and all with the desire to love and write poetry. The quality of the poems may've been all over the place, ranging from a crow on a fence at sunset (worthy of Bashō), to Mickey Mouse, to how a country row of mailboxes resembled gravestones, to teenage heartbreak. My students were wonderfully generous and helpful with each other, always self-deprecating, eager to learn, to improve, to express their visions. They were also tolerant of and patient with my not-well-informed but well-meaning suggestions. That class was a highlight of my life and it all blossomed from a shared love, not hatred, of poetry. Ben Lerner in The Hatred of Poetry seems to believe that poetry deserves to be hated, but to me this is mean-spirited. Small minded. More clever than meaningful. But an excellent way for an academic to get a grant. Ben Lerner's thesis rests on two fallible points: first, that poets, unlike other artists, fail to achieve the transformation of their poetic vision into substance. But all artists suffer this frustration. How many painters have taken knives to canvas? How many novels have been burned in manuscript? How many songs died aborning, never being heard? (In fact, Lerner's root example is song, not poetry.) As George Orwell said, "Every book is a failure." Or William Faulkner: "We will all agree that we failed. That what we made never ... will match the shape, the dream of perfection which ... will continue to drive us, even after each failure, until anguish frees us and the hand falls still at last." Or da Vinci: "Art is never finished, only abandoned." I can't say that any poet is a greater or more frustrated artist than Toni Morrison, Pablo Picasso, Beethoven, or Yo-Yo Ma. Lerner's second point is that poets must be simultaneously relevant and universal. Yet so much amazing poetry is neither and never attempted to be either. Much reasonably modern poetry (yes, you, Language Poetry) is completely opaque. It's neither relevant nor universal, but is certainly poetry (no, I'm not a fan, 'nuff said). There are other odd moments: Lerner eviscerates a fellow white male poet for being more of a white male than he. As a poet he's ready to leap into the cliche simile of "like a sensation in a phantom limb." And while he appreciates Dickinson he finds Whitman wanting because "Whitman's dreamed union never arrived." Yet he seems to miss that Dickinson's tiny, hermetic, insular poems spoke to the broadest universal themes and passions, while Whitman's Old Testament prophet voice spoke to a very individual and personal, almost confessional view of himself: the great "I" as well as "We." He does note Charles Olson's accurate observation that lines of poems are more poetically striking when quoted in prose than in the actual source poem itself; I've always found that true and puzzling. My thought here is not to discourage anyone from reading The Hatred of Poetry. It's worth reading. But pack a rucksack full of salt, keep your skepticism at hand, and always, always, always question authority. The moments I've had reading Lorca, Dickinson, Neruda, and too many others are moments I treasure. Just read "Death of a Son" by Jon Silkin, and who could hate poetry? [3★]

Wednesday, April 25, 2018

Orwell on Truth by George Orwell (2018)

A short collection of commentaries on truth by the author of 1984 and Animal Farm.

Book Review: Orwell on Truth is a small, odd book, but no less interesting and valuable for that. This volume was deliberately gathered to address our "alternative facts" and "fake news" era, or should I just say misinformation, propaganda, and lies? Sadly, Orwell's thoughts are equally on point now as when they were originally written in response to Nazism and Stalinism. One of history's passionately committed writers, Orwell's great enemy was totalitarianism and fascism, whether capitalist or communist. He despised the disregard for truth which is fascism's sharpest tool. Orwell on Truth includes excerpts from throughout his writing career, including his novels. He writes about other truth-seekers of the time, such as Upton Sinclair. Orwell notes that those most ready to believe the unbelievable are "the poor, the ill-educated and above all, people who were economically insecure or had unhappy private lives." He notes that the unjust are always willing to defend the indefensible. Another observation is "already there are countless people who would think it scandalous to falsify a scientific textbook, but would see nothing wrong in falsifying a historical fact." Both happen in America. A few other of his thoughts:

>Democratic methods are only possible where there is a fairly large basis of agreement between all political parties.

>Totalitarianism ... declares itself infallible, and at the same time it attacks the very concept of objective truth.

>Our social structure ... is founded on cheap coloured labour.

>This kind of thing is frightening to me, because it often gives me the feeling that the very concept of objective truth is fading out of the world.

>The thing that strikes me more and more ...is the extraordinary viciousness and dishonesty of political controversy.

>[They] can survive almost any mistake because their more devoted followers do not look to them for an appraisal of the facts but for the stimulation of nationalistic loyalties.

>There is always a temptation to claim that any book whose tendency one disagrees with must be a bad book from a literary point of view.

>A genuinely unfashionable opinion is almost never given a fair hearing.

Orwell writes of the importance of moral fiction and moral writing in general: "No one ever wrote a great book in praise of the Inquisition." Orwell on Truth was an invaluable resource for finding parallels between our time and the period before and during the Second World War, an educational and interesting read. But when finished, I wasn't sure exactly what to with it, except as a call to avoid being condemned to repeat the past. [3★]

Book Review: Orwell on Truth is a small, odd book, but no less interesting and valuable for that. This volume was deliberately gathered to address our "alternative facts" and "fake news" era, or should I just say misinformation, propaganda, and lies? Sadly, Orwell's thoughts are equally on point now as when they were originally written in response to Nazism and Stalinism. One of history's passionately committed writers, Orwell's great enemy was totalitarianism and fascism, whether capitalist or communist. He despised the disregard for truth which is fascism's sharpest tool. Orwell on Truth includes excerpts from throughout his writing career, including his novels. He writes about other truth-seekers of the time, such as Upton Sinclair. Orwell notes that those most ready to believe the unbelievable are "the poor, the ill-educated and above all, people who were economically insecure or had unhappy private lives." He notes that the unjust are always willing to defend the indefensible. Another observation is "already there are countless people who would think it scandalous to falsify a scientific textbook, but would see nothing wrong in falsifying a historical fact." Both happen in America. A few other of his thoughts:

>Democratic methods are only possible where there is a fairly large basis of agreement between all political parties.

>Totalitarianism ... declares itself infallible, and at the same time it attacks the very concept of objective truth.

>Our social structure ... is founded on cheap coloured labour.

>This kind of thing is frightening to me, because it often gives me the feeling that the very concept of objective truth is fading out of the world.

>The thing that strikes me more and more ...is the extraordinary viciousness and dishonesty of political controversy.

>[They] can survive almost any mistake because their more devoted followers do not look to them for an appraisal of the facts but for the stimulation of nationalistic loyalties.

>There is always a temptation to claim that any book whose tendency one disagrees with must be a bad book from a literary point of view.

>A genuinely unfashionable opinion is almost never given a fair hearing.

Orwell writes of the importance of moral fiction and moral writing in general: "No one ever wrote a great book in praise of the Inquisition." Orwell on Truth was an invaluable resource for finding parallels between our time and the period before and during the Second World War, an educational and interesting read. But when finished, I wasn't sure exactly what to with it, except as a call to avoid being condemned to repeat the past. [3★]

Monday, April 23, 2018

Thoughts About Reading ... #4

Sometimes thoughts arrive for no particular reason, and on the off chance that I'm not the only one thinking too much, here are a few ideas that have shown up lately ...

First, I wonder does your Myers Briggs defined personality determine what you like to read? For instance, would a INTJ personality type enjoy plot-driven fiction or nonfiction, while an ESFJ likes cozy, mushy prose? How about political leanings? Do members of one party read caring, sharing, and helpful books, while members of another party not read books at all? I know there's a blood-type diet, but I have trouble imagining that a book subscription service could make a fortune that way. And I'm kind of surprised in this era of cyber info hoarding that readers aren't having our reading tastes sliced and diced, or are we?

Next, how come there are books that are admirable and brilliantly written, but just aren't a lot of fun. Yes, I'm looking at you Toni Morrison. She's great in the real meaning of that word. She's perhaps the greatest American author of our time (don't forget that Nobel Prize), but her books are a good read on a whole 'nother level than Attica Locke. It's like Morrison is me eating my veg and taking my vitamins, while Louise Penny's books are dessert. Shakespeare (like Toni Morrison) is a great writer, but his plays are work! Some of the classics just aren't very enjoyable to me on a shallow level. I can recognize the greatness, appreciate the quality writing and the important themes, but they don't always keep me on the edge of my seat. Lately I've been thinking of reading William Faulkner and I'm afraid that ... .

Finally, I was reading several of Shakespeare's plays and found the Folger series was the most accessible and helpful for me. There may be other series geared more to PhD candidates, but these are excellent for the common reader. Take a look. They have the notes on the facing page, which is brilliant, there are occasional illustrations, and also essays front and back. The trade paperback size is nicer than the mass market size, with better paper, larger font, and still quite reasonably priced. Unfortunately Folger don't seem to be making the trade size anymore, so you may have to scout out thrift stores and charity shops. And yes, Mr. Folger was related to the coffee people, but not to their money.

Well, that's enough thinking for now. See you soon! 🐢

First, I wonder does your Myers Briggs defined personality determine what you like to read? For instance, would a INTJ personality type enjoy plot-driven fiction or nonfiction, while an ESFJ likes cozy, mushy prose? How about political leanings? Do members of one party read caring, sharing, and helpful books, while members of another party not read books at all? I know there's a blood-type diet, but I have trouble imagining that a book subscription service could make a fortune that way. And I'm kind of surprised in this era of cyber info hoarding that readers aren't having our reading tastes sliced and diced, or are we?

Next, how come there are books that are admirable and brilliantly written, but just aren't a lot of fun. Yes, I'm looking at you Toni Morrison. She's great in the real meaning of that word. She's perhaps the greatest American author of our time (don't forget that Nobel Prize), but her books are a good read on a whole 'nother level than Attica Locke. It's like Morrison is me eating my veg and taking my vitamins, while Louise Penny's books are dessert. Shakespeare (like Toni Morrison) is a great writer, but his plays are work! Some of the classics just aren't very enjoyable to me on a shallow level. I can recognize the greatness, appreciate the quality writing and the important themes, but they don't always keep me on the edge of my seat. Lately I've been thinking of reading William Faulkner and I'm afraid that ... .

Finally, I was reading several of Shakespeare's plays and found the Folger series was the most accessible and helpful for me. There may be other series geared more to PhD candidates, but these are excellent for the common reader. Take a look. They have the notes on the facing page, which is brilliant, there are occasional illustrations, and also essays front and back. The trade paperback size is nicer than the mass market size, with better paper, larger font, and still quite reasonably priced. Unfortunately Folger don't seem to be making the trade size anymore, so you may have to scout out thrift stores and charity shops. And yes, Mr. Folger was related to the coffee people, but not to their money.

Well, that's enough thinking for now. See you soon! 🐢

Saturday, April 21, 2018

The Catcher in the Rye by J. D. Salinger (1951)

Holden Caulfield is kicked out of school and tries to find home.

Book Review: The Catcher in the Rye is one of those marmite books, readers love it or hate it. I'm in the first camp, but why? I don't identify with Holden. We have almost no similarities. Of course I can relate to teenage angst, but mine was completely different. I can understand Holden, however, and can see him slowly falling apart, falling into a quicksand of depression, with no way to stop or control it. Some readers whine about his whining, but he isn't -- he's disintegrating. "Disappearing." He's sad, and that is relatable. If your sense of humor extends to sarcasm, he's also funny as hell. Alternately, he's despairing and vulnerable as hell. Some readers may see the ducks in Central Park, Allie's baseball glove, Holden's red hat as symbols, but maybe not, they don't have to represent anything. Each is simply part of Holden's personality, his mental issues, his unconscious. He clings to Allie's baseball glove as part of Allie, a memory, of simpler, happier times past, of childhood. Holden worries about the ducks, obsesses actually, because he's worried about everyone weak and helpless, like the children in the rye, like himself. Holden likes his hat because it's unique and different, makes him an individual, shows he doesn't care what people think, although he really does. Holden wants everything to stop changing: "Certain things they should stay the way they are ... I know that's impossible, but it's too bad anyway." Change involves growing up, losing loved ones, everyone becoming different people. The Catcher in the Rye is best read between the ages of 13 and 18 (the same ages when our musical tastes form). But it's rewarding at any age, because although this is a book about a teenager, and a teenager's confusion, it was written by a man who had survived a war. (Salinger landed on D-Day, fought in the Battle of the Bulge (the bloodiest U.S. battle in World War II), and helped liberate Dachau.) Somehow, those experiences are also part of Holden Caulfield and part of The Catcher in the Rye. [5★]

Book Review: The Catcher in the Rye is one of those marmite books, readers love it or hate it. I'm in the first camp, but why? I don't identify with Holden. We have almost no similarities. Of course I can relate to teenage angst, but mine was completely different. I can understand Holden, however, and can see him slowly falling apart, falling into a quicksand of depression, with no way to stop or control it. Some readers whine about his whining, but he isn't -- he's disintegrating. "Disappearing." He's sad, and that is relatable. If your sense of humor extends to sarcasm, he's also funny as hell. Alternately, he's despairing and vulnerable as hell. Some readers may see the ducks in Central Park, Allie's baseball glove, Holden's red hat as symbols, but maybe not, they don't have to represent anything. Each is simply part of Holden's personality, his mental issues, his unconscious. He clings to Allie's baseball glove as part of Allie, a memory, of simpler, happier times past, of childhood. Holden worries about the ducks, obsesses actually, because he's worried about everyone weak and helpless, like the children in the rye, like himself. Holden likes his hat because it's unique and different, makes him an individual, shows he doesn't care what people think, although he really does. Holden wants everything to stop changing: "Certain things they should stay the way they are ... I know that's impossible, but it's too bad anyway." Change involves growing up, losing loved ones, everyone becoming different people. The Catcher in the Rye is best read between the ages of 13 and 18 (the same ages when our musical tastes form). But it's rewarding at any age, because although this is a book about a teenager, and a teenager's confusion, it was written by a man who had survived a war. (Salinger landed on D-Day, fought in the Battle of the Bulge (the bloodiest U.S. battle in World War II), and helped liberate Dachau.) Somehow, those experiences are also part of Holden Caulfield and part of The Catcher in the Rye. [5★]

Thursday, April 19, 2018

The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath (1963)

In 1953, nineteen year old Esther Greenwood confronts an overwhelming world.

Book Review: The Bell Jar is an amazing book, much more than even its author thought it could be. While she and husband Ted Hughes thought of it as a "potboiler" (written simply for money by appealing to common taste), Plath's writing, insights, and intelligence make it necessary. I first read it when I was about 13, and wondered if I would now find it too simple or juvenile, but found just the opposite. This book was far ahead of its time; it's bewildering that it could've been written in 1963. Written when emotional problems were kept private and secret, the focus on mental health fits with many books written today, and the description of depression and confusion are accurate and affecting: "I felt very still and very empty, the way the eye of a tornado must feel, moving dully along in the middle." Class conflict occurs: Esther is a "scholarship student" surrounded by posh girls, "bored with flying around in airplanes and bored with skiing in Switzerland at Christmas and bored with the men in Brazil." Although The Bell Jar was released the same year as The Feminine Mystique (which signaled the second struggle for women's rights in America), Esther Greenwood determinedly asserts herself as a woman: "I thought it sounded like just the sort of drug a man would invent ... the drug would make her forget how bad the pain had been, when all the time, in some secret part of her, that long, blind, doorless and windowless corridor of pain was waiting to open up and shut her in again"; "The trouble was, I hated the idea of serving men in any way. I wanted to dictate my own letters"; "I couldn't stand the idea of a woman having to live a single pure life and a man being able to have a double life." The writing is alive and steadily evocative, the humor is dark and biting, intelligence informs every line. As in her poetry, Plath's vision of semiotics finds elements of Esther's life reflected in the events of the time. The brilliant first sentence foreshadows everything: "It was a queer, sultry summer, the summer they electrocuted the Rosenbergs, and I didn't know what I was doing in New York." Later one of her wealthy friends states: "It's awful such people should be alive." The Bell Jar is the best book I've read in a long time, combining a defiant story with a stinging slap of emotion. [5★]

Book Review: The Bell Jar is an amazing book, much more than even its author thought it could be. While she and husband Ted Hughes thought of it as a "potboiler" (written simply for money by appealing to common taste), Plath's writing, insights, and intelligence make it necessary. I first read it when I was about 13, and wondered if I would now find it too simple or juvenile, but found just the opposite. This book was far ahead of its time; it's bewildering that it could've been written in 1963. Written when emotional problems were kept private and secret, the focus on mental health fits with many books written today, and the description of depression and confusion are accurate and affecting: "I felt very still and very empty, the way the eye of a tornado must feel, moving dully along in the middle." Class conflict occurs: Esther is a "scholarship student" surrounded by posh girls, "bored with flying around in airplanes and bored with skiing in Switzerland at Christmas and bored with the men in Brazil." Although The Bell Jar was released the same year as The Feminine Mystique (which signaled the second struggle for women's rights in America), Esther Greenwood determinedly asserts herself as a woman: "I thought it sounded like just the sort of drug a man would invent ... the drug would make her forget how bad the pain had been, when all the time, in some secret part of her, that long, blind, doorless and windowless corridor of pain was waiting to open up and shut her in again"; "The trouble was, I hated the idea of serving men in any way. I wanted to dictate my own letters"; "I couldn't stand the idea of a woman having to live a single pure life and a man being able to have a double life." The writing is alive and steadily evocative, the humor is dark and biting, intelligence informs every line. As in her poetry, Plath's vision of semiotics finds elements of Esther's life reflected in the events of the time. The brilliant first sentence foreshadows everything: "It was a queer, sultry summer, the summer they electrocuted the Rosenbergs, and I didn't know what I was doing in New York." Later one of her wealthy friends states: "It's awful such people should be alive." The Bell Jar is the best book I've read in a long time, combining a defiant story with a stinging slap of emotion. [5★]

Monday, April 16, 2018

National Poetry Month 2018!

"April is the cruelest month" ... because we make you read poetry for National Poetry Month? Well, maybe not. Thanks to Rupi Kaur poetry has had a recent resurgence. While not the biggest Kaur fan, I truly appreciate the attention she's brought and hope that her Tumblresque poetry, derivative as it may be, can be a stepping stone for her readers and fans to other poets and poetry. Along with that hope, here's a thought about how to get into the foreign land that is poetry. Most poetry books are actually quite short, slim little volumes that are perfect for leveling a table. If the poet gains some small measure of success, there will often later be collections of these slender books into an omnibus "Selected Poems" or "Collected Poems" by the poet. Although you may be tempted to get more bang for your buck by buying the larger collection, think twice. I find the larger collections difficult to read: there's just too much. It may be easier to read the smaller volumes, certainly less intimidating, and often the single editions have a theme or consistency that reveal an intent for the poems to function together, a suite or progression of poems. With the small books, the end is always in sight, even if they are overpriced (thrift stores and used-book shops are one answer). I can't lie, I have purchased the larger volumes from time to time, and found it best for me just to keep one on my bedside table to dip into at random, here and there, reading two or three before turning to another book or sleep. My fear is I'll never finish the collection. You may find your reading is different, more disciplined and regular, than mine. Happy NPM! 🐢

Thursday, April 12, 2018

Lust, Caution by Eileen Chang (1979)

A spy story, a love story.

Story Review: Lust, Caution is either a long story or a short novella. I prefer to think of it as a story because it is one of those classic writings that include so much in so little. That, like an Emily Dickinson poem, captures a whole universe in a single grain of sand. Within what seems like a thriller, a spy or war story, Eileen Chang (Zhang Ailing) addresses the role of women, the role of the individual, balances love and politics and death. In Lust, Caution Chang wrote a story about political strife (often present though tangential in her stories), but then showed that her usual subjects of love, connections between women and men, a woman's place, are equally important. She demonstrates how the choices of an individual, Chia-chih, a woman, are as important as any other part of the puzzle. All rests on the single decision, the single word, of a single person, every detail described with stunning realism. For me, Lust, Caution extends out in all directions, to alternate histories and futures, to alternate possibilities of what may or should've happened, to why Chia-chih made her decision. Also a 2007 film directed by Ang Lee. [5★]

Story Review: Lust, Caution is either a long story or a short novella. I prefer to think of it as a story because it is one of those classic writings that include so much in so little. That, like an Emily Dickinson poem, captures a whole universe in a single grain of sand. Within what seems like a thriller, a spy or war story, Eileen Chang (Zhang Ailing) addresses the role of women, the role of the individual, balances love and politics and death. In Lust, Caution Chang wrote a story about political strife (often present though tangential in her stories), but then showed that her usual subjects of love, connections between women and men, a woman's place, are equally important. She demonstrates how the choices of an individual, Chia-chih, a woman, are as important as any other part of the puzzle. All rests on the single decision, the single word, of a single person, every detail described with stunning realism. For me, Lust, Caution extends out in all directions, to alternate histories and futures, to alternate possibilities of what may or should've happened, to why Chia-chih made her decision. Also a 2007 film directed by Ang Lee. [5★]

Monday, April 9, 2018

The Missing Girl by Shirley Jackson (2018)

Three stories by the brilliant American chronicler of the damaged psyche.

Book Review: The Missing Girl is a starter, an appetizer, a quick and easy introduction to the work of Shirley Jackson, the author of The Haunting of Hill House (1959) and We Have Always Lived in the Castle (1962). Notably excluded is her best and most (in)famous story, "The Lottery." Jackson's writing tends to fall into three categories: (1) the psychologically damaged young woman confronting an overwhelming world; (2) the normal, if naive, person whose life becomes confounding and untenable; and (3) the endearing, often humorous tales characteristic of her nonfiction about children as collected in Life Among the Savages (1953) and Raising Demons (1957). In The Missing Girl we have an example of each type. The title tale, published in Fantasy and Science Fiction magazine in 1957, describes a girls' summer camp and reveals that our existence may not be as significant as we think. Perhaps life is more ephemeral and fragmented, perhaps some people are just barely here when other people are so self-absorbed. "Journey with a Lady," published in Harper's in 1952, falls into the third category: accessible, amusing, a slice of life. The third story, "Nightmare," fits into the second category. Unpublished until 1998, an average young woman finds that the city can be unwelcoming and bewildering -- sometimes paranoia is real. All three stories were included in the generous 1998 anthology of unpublished and published-but-uncollected stories edited by two of her children, Just an Ordinary Day. Jackson is sometimes classified as a horror writer. But rather than being scary or gory, her work is more an exploration of psychological dread and damage. If this inexpensive and entertaining selection sparks your interest, rest assured that Jackson's several other compilations, such as The Lottery and Other Stories, Come Along with Me, or Dark Tales, will provide equally varied and equally good and even better stories than those in The Missing Girl. [4★]

Book Review: The Missing Girl is a starter, an appetizer, a quick and easy introduction to the work of Shirley Jackson, the author of The Haunting of Hill House (1959) and We Have Always Lived in the Castle (1962). Notably excluded is her best and most (in)famous story, "The Lottery." Jackson's writing tends to fall into three categories: (1) the psychologically damaged young woman confronting an overwhelming world; (2) the normal, if naive, person whose life becomes confounding and untenable; and (3) the endearing, often humorous tales characteristic of her nonfiction about children as collected in Life Among the Savages (1953) and Raising Demons (1957). In The Missing Girl we have an example of each type. The title tale, published in Fantasy and Science Fiction magazine in 1957, describes a girls' summer camp and reveals that our existence may not be as significant as we think. Perhaps life is more ephemeral and fragmented, perhaps some people are just barely here when other people are so self-absorbed. "Journey with a Lady," published in Harper's in 1952, falls into the third category: accessible, amusing, a slice of life. The third story, "Nightmare," fits into the second category. Unpublished until 1998, an average young woman finds that the city can be unwelcoming and bewildering -- sometimes paranoia is real. All three stories were included in the generous 1998 anthology of unpublished and published-but-uncollected stories edited by two of her children, Just an Ordinary Day. Jackson is sometimes classified as a horror writer. But rather than being scary or gory, her work is more an exploration of psychological dread and damage. If this inexpensive and entertaining selection sparks your interest, rest assured that Jackson's several other compilations, such as The Lottery and Other Stories, Come Along with Me, or Dark Tales, will provide equally varied and equally good and even better stories than those in The Missing Girl. [4★]

Friday, April 6, 2018

"Girl" by Jamaica Kincaid (1978)

A mother's instructions to her daughter on how to live and behave.

Story Review: "Girl" is a brilliant story. Wonderfully, it's often taught in schools. The story accomplishes so much by doing very little. Everything is done through indirection, between the lines. Superficially, it's simply a single sentence: a mother's guidance, a long series of instructions, suggestions, directions, household hints and tips (the daughter gets in only two short responses). Rules. "Soak salt fish overnight," "wash the color clothes on Tuesday," "this is how you set a table for dinner," "this is how you sweep a corner." Some of the instructions are good, "don't walk barehead in the hot sun," "this is how you smile to someone you don't like too much," "don't throw stones at blackbirds, because it might not be a blackbird at all." Within those instructions is a powerful and insidious critique of women's place in society. The reader reaches every conclusion about "Girl" alone, as though the thoughts sprung fully formed within her own synapses. Which, of course, is the best way to present a diatribe: without the diatribe. The story is hard and fast, like a bullet to the brain. At first the mother's guidance seems helpful and clever, how to perform various household chores. But two different themes soon arise. First, that the daughter's life will wholly consumed with cooking, cleaning, sewing, and serving. The daughter's only future is woman's work, the same as her mother's life. There is nothing about reading, learning, thinking, growing, aspiring. It's too easy to see the mother as the villain of the piece, but she's not. Her guidance stems from all she's ever known, and if it seems harsh it's only because she's learned, she knows how to survive in a small, traditional community. The mother is only teaching what she's known, she is not trying to limit her daughter, only teach her the rules of society. But then there are lines that belie the traditional guidance, moving from how to iron her father's clothes to "this is how you smile to someone you don't like at all," "this is how to make a good medicine to throw away a child before it even becomes a child," "this is how to bully a man," "this is how to love a man ... and if they don't work don't feel too bad about giving up." These survival skills are a bit more revolutionary. Jamaica Kincaid is a good enough writer to introduce complexity into the mother: yes she's preparing her daughter for a traditional life, but she may also be giving her some tools to circumvent the rules. The second theme, like a slap in the face, is that the daughter should become and behave as a proper lady ("not like the slut you are so bent on becoming"), but then also teaches her "how to spit up in the air if you feel like it." While I read that as being only if no one is looking, who knows? That this is an Antiguan story creates one layer of meaning here, but it's also a universal story about the future of any girl in any society: will I be limited to a certain kind of life or can there be more? This story is contained in Kincaid's collection At the Bottom of the River. "Girl" is one of the great stories of our time, or any time. [5★]

Story Review: "Girl" is a brilliant story. Wonderfully, it's often taught in schools. The story accomplishes so much by doing very little. Everything is done through indirection, between the lines. Superficially, it's simply a single sentence: a mother's guidance, a long series of instructions, suggestions, directions, household hints and tips (the daughter gets in only two short responses). Rules. "Soak salt fish overnight," "wash the color clothes on Tuesday," "this is how you set a table for dinner," "this is how you sweep a corner." Some of the instructions are good, "don't walk barehead in the hot sun," "this is how you smile to someone you don't like too much," "don't throw stones at blackbirds, because it might not be a blackbird at all." Within those instructions is a powerful and insidious critique of women's place in society. The reader reaches every conclusion about "Girl" alone, as though the thoughts sprung fully formed within her own synapses. Which, of course, is the best way to present a diatribe: without the diatribe. The story is hard and fast, like a bullet to the brain. At first the mother's guidance seems helpful and clever, how to perform various household chores. But two different themes soon arise. First, that the daughter's life will wholly consumed with cooking, cleaning, sewing, and serving. The daughter's only future is woman's work, the same as her mother's life. There is nothing about reading, learning, thinking, growing, aspiring. It's too easy to see the mother as the villain of the piece, but she's not. Her guidance stems from all she's ever known, and if it seems harsh it's only because she's learned, she knows how to survive in a small, traditional community. The mother is only teaching what she's known, she is not trying to limit her daughter, only teach her the rules of society. But then there are lines that belie the traditional guidance, moving from how to iron her father's clothes to "this is how you smile to someone you don't like at all," "this is how to make a good medicine to throw away a child before it even becomes a child," "this is how to bully a man," "this is how to love a man ... and if they don't work don't feel too bad about giving up." These survival skills are a bit more revolutionary. Jamaica Kincaid is a good enough writer to introduce complexity into the mother: yes she's preparing her daughter for a traditional life, but she may also be giving her some tools to circumvent the rules. The second theme, like a slap in the face, is that the daughter should become and behave as a proper lady ("not like the slut you are so bent on becoming"), but then also teaches her "how to spit up in the air if you feel like it." While I read that as being only if no one is looking, who knows? That this is an Antiguan story creates one layer of meaning here, but it's also a universal story about the future of any girl in any society: will I be limited to a certain kind of life or can there be more? This story is contained in Kincaid's collection At the Bottom of the River. "Girl" is one of the great stories of our time, or any time. [5★]

Wednesday, April 4, 2018

Half a Lifelong Romance by Eileen Chang (1948)

In the years before the Second World War a young woman and man fall for each other, but learn that the course of true love never did run smooth.

Book Review: Half a Lifelong Romance is a story of thwarted love. A heartbreaking combination of Jane Austen and Thomas Hardy. Throw in Gone With the Wind and a bit of Shakespeare as well. Eileen Chang's focus is love, romance, and marriage, but here that unholy trinity is the gateway to a life of submission, suffering, and sorrow: "All they'd had was a little piece of happiness, a moment that passed all too quickly." The lovers' own hesitation first separates them, but then the twin evils of greed and war complete the division, and lead them into a world where a love meant to be, fails. Constant societal pressures compound the tragedy. At the same time, China is undergoing significant changes, still modernizing and Westernizing, while retaining many of the difficulties and obstacles for women, becoming an almost winless situation, unless one is lucky enough to become a mother-in-law in a comfortable family. The vast divide between rich and poor is also displayed (although servants can be surprisingly outspoken). Half a Lifelong Romance is a story of unrequited, unspoken love, and selfish, horrific betrayal. Ill fated from the beginning. The theme of love denied is repeated and interwoven, afflicting Manlu and Yujin; Shuhui and Tsuizhi; and most notably the star-crossed lovers, Manzhen and Shijun. Chang reveals complex emotions throughout a complex plot of "birth, old age, illness, death." There are extended families, military battles, good and evil. The cruelty of selfishness recurs, many characters trying to manipulate others for their own self-interest. A nice feature was the chaste love between the characters, putting the focus on the emotional rather than the physical, and also interesting that (the worst kind of) lust is presented as like an illness. Much folk wisdom is sprinkled throughout Half a Lifelong Romance: "an invalid soon becomes a physician"; "wine goes to the stomach, worries are in the heart." One truth is "the poor are more than willing to help each other in times of need ... theirs is not the sympathy of the rich, all shriveled up with reservations and inhibitions." The translation is modern ("wimp," "drama queen") and British ("oi," "podgy," "in hospital"). Eileen Chang, or our omniscient narrator, is wise, aware, and thoughtful; a great teacher. In the end fate wins out and all the characters' pitiful striving is just food for the laughter of the gods: "The times spent looking forward to something would be his happiest times with her; their Sunday would never dawn." [4½★]

Book Review: Half a Lifelong Romance is a story of thwarted love. A heartbreaking combination of Jane Austen and Thomas Hardy. Throw in Gone With the Wind and a bit of Shakespeare as well. Eileen Chang's focus is love, romance, and marriage, but here that unholy trinity is the gateway to a life of submission, suffering, and sorrow: "All they'd had was a little piece of happiness, a moment that passed all too quickly." The lovers' own hesitation first separates them, but then the twin evils of greed and war complete the division, and lead them into a world where a love meant to be, fails. Constant societal pressures compound the tragedy. At the same time, China is undergoing significant changes, still modernizing and Westernizing, while retaining many of the difficulties and obstacles for women, becoming an almost winless situation, unless one is lucky enough to become a mother-in-law in a comfortable family. The vast divide between rich and poor is also displayed (although servants can be surprisingly outspoken). Half a Lifelong Romance is a story of unrequited, unspoken love, and selfish, horrific betrayal. Ill fated from the beginning. The theme of love denied is repeated and interwoven, afflicting Manlu and Yujin; Shuhui and Tsuizhi; and most notably the star-crossed lovers, Manzhen and Shijun. Chang reveals complex emotions throughout a complex plot of "birth, old age, illness, death." There are extended families, military battles, good and evil. The cruelty of selfishness recurs, many characters trying to manipulate others for their own self-interest. A nice feature was the chaste love between the characters, putting the focus on the emotional rather than the physical, and also interesting that (the worst kind of) lust is presented as like an illness. Much folk wisdom is sprinkled throughout Half a Lifelong Romance: "an invalid soon becomes a physician"; "wine goes to the stomach, worries are in the heart." One truth is "the poor are more than willing to help each other in times of need ... theirs is not the sympathy of the rich, all shriveled up with reservations and inhibitions." The translation is modern ("wimp," "drama queen") and British ("oi," "podgy," "in hospital"). Eileen Chang, or our omniscient narrator, is wise, aware, and thoughtful; a great teacher. In the end fate wins out and all the characters' pitiful striving is just food for the laughter of the gods: "The times spent looking forward to something would be his happiest times with her; their Sunday would never dawn." [4½★]

Monday, April 2, 2018

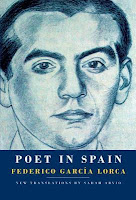

Poet in Spain by Federico Garcia Lorca (2017)

A new selection in English of works by one of Spain's greatest poets.

Poetry Review: Poet in Spain is a new translation (by Sarah Arvio) of a variety of works by my favorite poet, Federico Garcia Lorca. She includes a section ("Poems") containing a large, personal selection of poems from various of Lorca's works; a generous selection from Poem of the Deep Song (Poema del cante jondo); all of the Gypsy Ballads (Primero romancero gitano); the Divan of the Tamarit (Divan del Tamarit); the Lament for Ignacio Sanchez Mejias (Llanto por Ignacio Sanchez Mejias); the Sonnets of Dark Love (Sonetos del amor oscuro); and a play, Blood Wedding (Bodas de sangre). This roster includes work from most of Lorca's career (the translator chose not to include poems from his Poet in New York as not being as "Spanish" as the poems she selected, in conformance with the volume's title).

Any collection of Lorca's work is worth reading. What's unique about Poet in Spain is the creative effort taken by the translator, Sarah Arvio, herself a published poet. Arvio has chosen to have Lorca's work conform to her artistic vision. A representative example is a short section (cited by Arvio herself) from the long poem Lament for Igancio Sanchez Mejias. Here Lorca expresses his horror even at the mere time of his friend's death:

Lorca's Original:

A las cinco de la tarde.

Ay que terribles cinco de la tarde!

Eran las cinco en todos los relojes!

Eran las cinco en sombra de la tarde!

Literal translation:

At five in the afternoon.

Ay that terrible five in the afternoon!

It was five on all the clocks!

It was five in the afternoon shade!

Arvio's translation:

At five o'clock

Ay what terrible fives

it was five on all the clocks

In the afternoon shadows

All translators make choices. Even for those who don't read Spanish, it's clear that Arvio has chosen to dispense with Lorca's punctuation. She also removes his variations on the refrain "five in the afternoon" (cinco de la tarde). Arvio's version seems more modern, cleaner perhaps, certainly more concise. But for me there's a loss. First, is simply the accurate representation of Lorca's creation. But second is the rhythm, the drumbeat, the repetition that emphasizes the poet's horror, the music of Lorca's words. Mejias was a matador, which influences both the importance of the time and my translation of sombra as "shade" instead of "shadow" (both are literally correct).

Arvio herself states of her translations: "I've used almost no punctuation; this was my style of composition." (Lorca's punctuation could be quite lively.) "I didn't imitate or replicate Lorca's prosodic strategies directly. I tried to reflect the poems -- to catch their essence."

Readers may appreciate Arvio's interpretations of Lorca's poetry and a more contemporary accessibility. If they buy this book, however, they should do so aware that at times these translations may not closely reflect Lorca's words and so (arguably) may not capture his meaning. This may not be the volume to cite when quoting Lorca in an academic paper. Many translators attempt to remain invisible, to create as little distance as possible between the words of the poet and the reader. Here Sarah Arvio makes herself visible as a poet. As such, some of these poems are more variations or "imitations" (as Robert Lowell called them). Although Arvio's style of translation is not the same as mine, Poet in Spain is clearly a labor of love, taking the time to translate a number of Lorca's poems, in fact complete books, including hard to find works. I'm happy to own it. For those interested in translations closer to Lorca's own creations, large editions of both Lorca's Selected Verse and Collected Poems are available in English from Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Additionally, both Oxford University Press and New Directions have excellent (smaller, cheaper) editions of Lorca's Selected Poems (either fits well in a backpack, purse, rucksack, or book bag). Every translator makes choices and can be second-guessed to death. Poet in Spain is a welcome addition to the debate. [3½★]

Poetry Review: Poet in Spain is a new translation (by Sarah Arvio) of a variety of works by my favorite poet, Federico Garcia Lorca. She includes a section ("Poems") containing a large, personal selection of poems from various of Lorca's works; a generous selection from Poem of the Deep Song (Poema del cante jondo); all of the Gypsy Ballads (Primero romancero gitano); the Divan of the Tamarit (Divan del Tamarit); the Lament for Ignacio Sanchez Mejias (Llanto por Ignacio Sanchez Mejias); the Sonnets of Dark Love (Sonetos del amor oscuro); and a play, Blood Wedding (Bodas de sangre). This roster includes work from most of Lorca's career (the translator chose not to include poems from his Poet in New York as not being as "Spanish" as the poems she selected, in conformance with the volume's title).

Any collection of Lorca's work is worth reading. What's unique about Poet in Spain is the creative effort taken by the translator, Sarah Arvio, herself a published poet. Arvio has chosen to have Lorca's work conform to her artistic vision. A representative example is a short section (cited by Arvio herself) from the long poem Lament for Igancio Sanchez Mejias. Here Lorca expresses his horror even at the mere time of his friend's death:

Lorca's Original:

A las cinco de la tarde.

Ay que terribles cinco de la tarde!

Eran las cinco en todos los relojes!

Eran las cinco en sombra de la tarde!

Literal translation:

At five in the afternoon.

Ay that terrible five in the afternoon!

It was five on all the clocks!

It was five in the afternoon shade!

Arvio's translation:

At five o'clock

Ay what terrible fives

it was five on all the clocks

In the afternoon shadows

All translators make choices. Even for those who don't read Spanish, it's clear that Arvio has chosen to dispense with Lorca's punctuation. She also removes his variations on the refrain "five in the afternoon" (cinco de la tarde). Arvio's version seems more modern, cleaner perhaps, certainly more concise. But for me there's a loss. First, is simply the accurate representation of Lorca's creation. But second is the rhythm, the drumbeat, the repetition that emphasizes the poet's horror, the music of Lorca's words. Mejias was a matador, which influences both the importance of the time and my translation of sombra as "shade" instead of "shadow" (both are literally correct).

Arvio herself states of her translations: "I've used almost no punctuation; this was my style of composition." (Lorca's punctuation could be quite lively.) "I didn't imitate or replicate Lorca's prosodic strategies directly. I tried to reflect the poems -- to catch their essence."

Readers may appreciate Arvio's interpretations of Lorca's poetry and a more contemporary accessibility. If they buy this book, however, they should do so aware that at times these translations may not closely reflect Lorca's words and so (arguably) may not capture his meaning. This may not be the volume to cite when quoting Lorca in an academic paper. Many translators attempt to remain invisible, to create as little distance as possible between the words of the poet and the reader. Here Sarah Arvio makes herself visible as a poet. As such, some of these poems are more variations or "imitations" (as Robert Lowell called them). Although Arvio's style of translation is not the same as mine, Poet in Spain is clearly a labor of love, taking the time to translate a number of Lorca's poems, in fact complete books, including hard to find works. I'm happy to own it. For those interested in translations closer to Lorca's own creations, large editions of both Lorca's Selected Verse and Collected Poems are available in English from Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Additionally, both Oxford University Press and New Directions have excellent (smaller, cheaper) editions of Lorca's Selected Poems (either fits well in a backpack, purse, rucksack, or book bag). Every translator makes choices and can be second-guessed to death. Poet in Spain is a welcome addition to the debate. [3½★]

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)